ISIS did a lot of destruction in Syria and Iraq. Notably, they were unfortunately able to destroy some of the worlds richest archeological and religious sites. Below is an unfinished list of UNESCO sites ISIS tried to destroy (emphasis on tried to). While many sites were looted, bombed or defaced, others proved too vast, solid, and enduring to be wiped out entirely.

Table of Contents

SYRIA

Palmyra

Palmyra is the single most important archaeological site from the Palmyrenes, and evidence of its existence dates back to early second millennium BCE and later fell under the control of the Roman Empire. Palmyra is located in far Central-Eastern Syria in the desert region, a vast arid area which made the location a popular place to stop for caravans tracking across Asia. In the 3rd century Palmyra saw a large increase of tax revenue thanks to their tax system and under the rule of Zenobia, Palmyra broke away from the Roman empire and the Palmyrian Empire was established.

Unfortunately this did not last long. In 273, Roman emperor Aurelian overthrew Zenobias government and largely destroyed the city. Zenobias fate was unknown and after the Timorids destroyed the city in 1400, Palmyra was reduced to a small village. In 1932, under the French mandate, Syrians were moved our to Tadmur (the local name for Palmyra city) and the city began to flourish with excavation activities and tourism.

Unfortunately, the city suffered greatly during the Syrian Civil War. In 2015, due to the cities geographical location, the city fell under control of ISIS and it was one of the largest sites ISIS tried to destroy. ISIS committed barbaric axts against the local population, city and ruins. One of the most notable people executed unjustly under ISIS rule was Khaled Al-Ass’ad, the former Director of Antiquities at Palmyra.

The Story of Khaled Al-Ass’ad

Khaled al-Ass’ad was a Syrian archaeologist whose life became inseparable from the ancient city of Palmyra. Born in 1934, he devoted more than 40 years to studying, preserving, and promoting the ruins, serving as Palmyra’s chief antiquities expert and later as head of its museum.

Under his guidance, the site became one of the Middle East’s most important archaeological centers, attracting international scholars and visitors while safeguarding priceless artifacts from looting and decay.

In 2015, when ISIS captured Palmyra, al-Ass’ad refused to abandon the city he had spent a lifetime protecting. Despite threats and interrogation, he would not reveal the locations of hidden artifacts that had been evacuated for safekeeping. For weeks he was held and pressured to betray the cultural heritage of his country. He did not.

On August 18, 2015, ISIS publicly executed him in Palmyra’s main square. He did not break or bend in face of hardship and gave his life for a cause he cared deeply about. He protected history, knowledge and the culture in his defiant stand against terrorism.

“I will die standing… the Palm Tree of Palmyra does not bend.”

Translated quote from Khaled al-Ass’ad before he was murdered by ISIS members

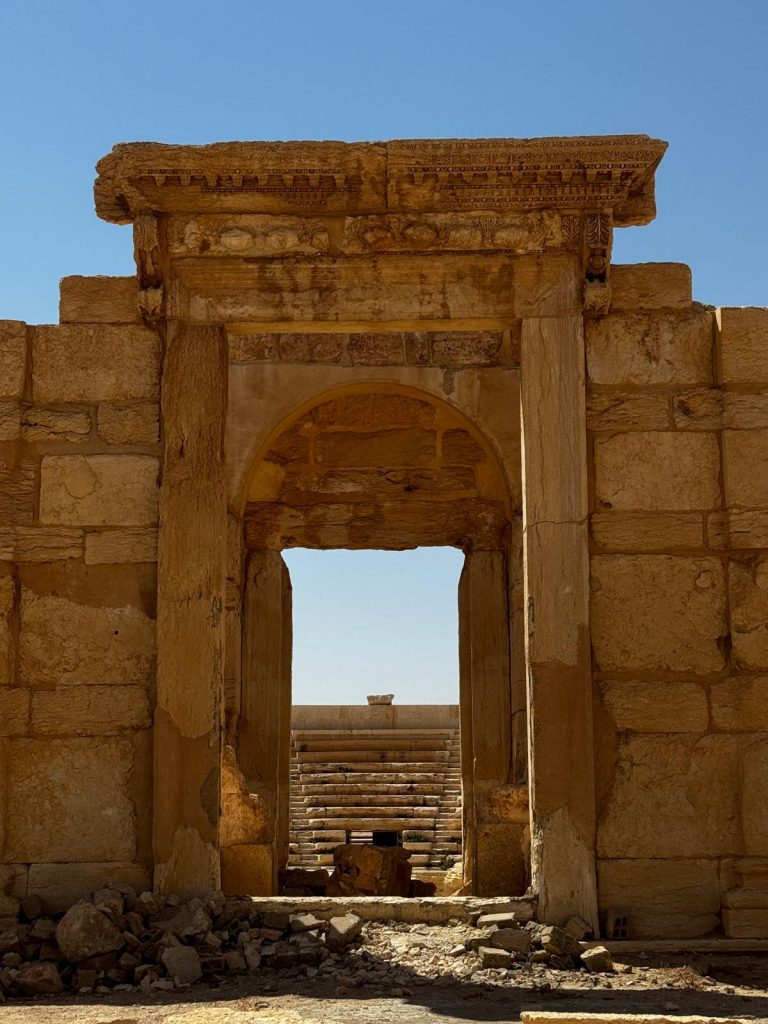

Destruction of Palmyra

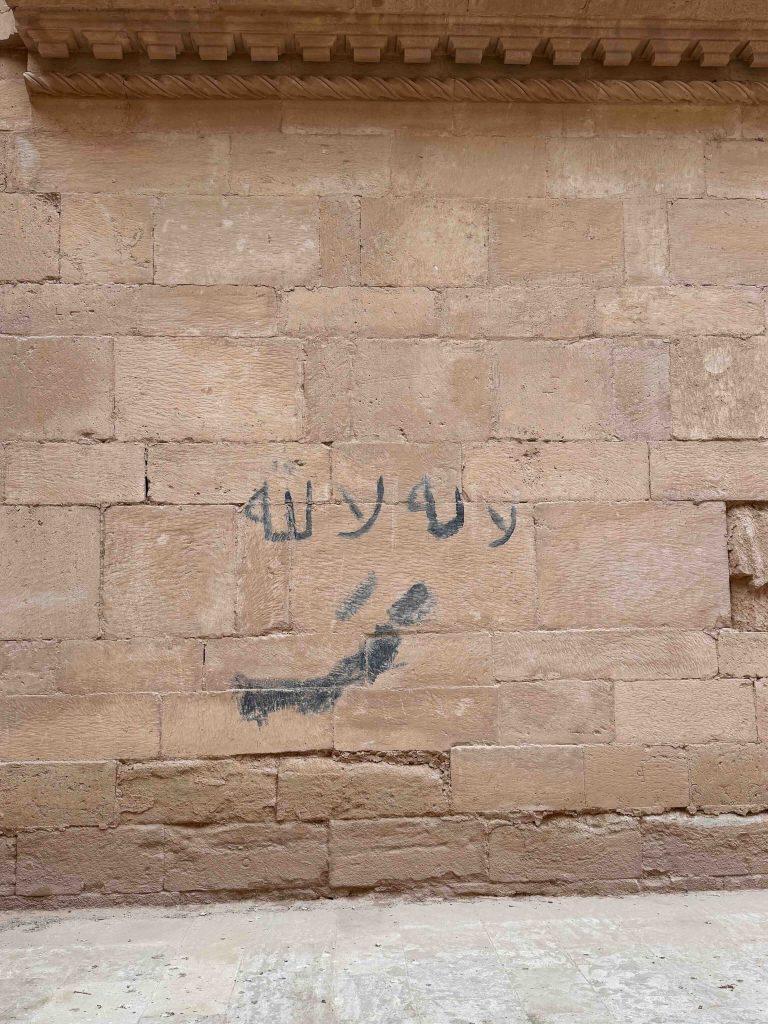

Sites ISIS tried to destroy in Palmyra include the Temples of Bel and Baalshamin, the tower tombs, the monumental arch, and entire rows of standing columns, while also looting the Palmyra Museum and destroying countless sculptures and artifacts left inside.

The site was recaptured by the Syrian Army in 2016 with the help of Russia. However, Palmyra had already faced significant damage. Tourism is slowly picking up however, with instability in Syria, it is nothing like it used to be.

There used to be tens of buses everyday come to Palmyra to visit. Now we are lucky if one small group comes in one day.

A local salesman recounted to me

Despite the damage, Palmyra remains open to visitors, with many original structures still standing, or partially standing. Remarkably, it’s estimated that nearly 80% of the ancient city lies hidden beneath the desert, yet to be excavated. This is proof that some things even ISIS could not destroy.

Mar Elian Monastery

Mar Elian Monastery, near Al-Qaryatayn in central Syria, dates back to the 5th century and is dedicated to Saint Elian, a local Christian martyr from the 3rd century. The monastery was once an important pilgrimage site, with a church, living quarters for monks, and a chapel holding the saint’s relics. Over time, it suffered from decay, looting, and, most recently, attacks during the Syrian conflict.

Destruction By ISIS

In 2015, Mar Elian Monastery joined the list of sites ISIS tried to destroy. ISIS occupied the site and ruined parts of the monastery, including the shrine. Despite the dMar Elian Monastery was hit hard during the Syrian conflict. ISIS bulldozed much of the monastery, tearing down walls, buildings, and the church itself, leaving the site in ruins.

Christian symbols and crosses were removed or defaced, and even the cemetery and gravestones were desecrated. Most heartbreakingly, the tomb of Saint Elian and his relics were damaged or disturbed. What once was a vibrant place of worship and pilgrimage was reduced to rubble, with very little of the original monastery still standing, a stark reminder of the cultural and religious heritage lost in the conflict.

Other Sites In Syria

There were hundreds of cities, towns and sites ISIS tried to destroy in Syria, predominately in the Central and North-East parts of Syria. This includes many ancient relics and sites in cities such as Raqqa, Dura-Europos and other cities that were damaged and looted during the war, although sometimes it is not exactly clear whether this was directly from ISIS or other non-state actors involved in the war.

IRAQ

Hatra

Hatra is perhaps one of the most underrated archeological sites in all of Mesopotamia and is one of the top must-see sites when visiting Iraq today. Alike Palmyra, Hatra is located in an arid area in the North-West area of Iraq, close to the border with Syria. Hatra came about as a place to stop for caravan traders, like Palmyra.

While much of Hatra’s past is unknown, some information about the city of Hatra reveals a prosperous past. The city began in the very early AD, thrived in the second century AD and fell in the third century AD. The Kingdom of Hatra fell due to the conquest of Shāpūr ruler of the Persian Sāsānian dynasty. There is, of course, a love story involved in the telling of Hatra’s demise. The daughter of the King of Hatra was said to have fallen for Shāpūr and allowed him to conquer the city.

The conquering included the ultimate death of her father, the King and led to the pair marrying and the end of the family’s rule in Hatra.

Like many ruins in Mesopotamia, Hatra was seemingly swallowed by the desert over time and was not discovered until the 19th century. Although, most of the ruins are still believed to be underground and are yet to be excavated. Some artifacts have been recovered over the years, as a result of different projects and many items remain in the Baghdad Museum.

Destruction By ISIS

ISIS occupied Hatra in the summer of 2014. They remained in control of the ancient city until it was liberated by Iraqi forces in April 2017.

ISIS used the sprawling site as a training ground rather than Hatra becoming one of the sites ISIS tried to destroy – like Palmyra. This tactic—stationing forces in historically significant ruins, similar to what they did in Palmyra, Syria—was intended to deter aerial strikes and attacks from other militias.

The strategy worked, and ISIS was able to occupy Hatra for several years. Unlike Palmyra, however, the destruction here was relatively limited. While statues and idols were decapitated or broken into smaller pieces, the pagan temple of Hatra and many other religious structures the group would have considered heretical largely survived.

Reconstruction Since 2016

Local archaeologists, working with UNESCO and international partners like the ALIPH Foundation, have documented the damage, cleared rubble, and removed dangerous unexploded ordnance from the site. Efforts have also focused on stabilizing crumbling walls and structures and conserving original architectural elements so that the ruins can endure for future generations.

Some reconstruction work has been carried out on specific elements, such as a portico column and architrave near the Temple of Shahiro, using original stones to ensure authenticity. Protective measures, including improved site infrastructure and controlled access, have also been implemented to prevent further harm. The goal has been to repair and preserve rather than erase or replace, keeping the ruins as close as possible to their historic state.

Nimrud and Khorsabad

Nimrud is an ancient Assyrian city located in northern Iraq, also known as Kalhu. It was a major capital of the Assyrian Empire, especially under kings like Ashurnasirpal II (9th century BCE). Nimrud is famous for its palaces, temples, massive walls, and iconic lamassu statues—the winged human-headed bulls that guarded entrances.

Khorsabad is the modern name for the Assyrian city of Dur-Sharrukin, built by Sargon II around 717 BCE as his new capital. Located in northern Iraq near Mosul, the city was carefully planned with wide streets, monumental palaces, temples, and fortified walls.

Like Nimrud, it featured lamassu statues and impressive reliefs, highlighting Assyrian art and architecture. Khorsabad was less of a long-term capital than Nimrud, as it was abandoned shortly after Sargon II’s death, but it remains one of the most important archaeological sites for understanding the Assyrian Empire.

Damage By ISIS

Unfortunately in 2015, both joined the list of sites ISIS tried to destroy. ISIS swept through the site and left a trail of devastation. Palaces reduced to rubble, lamassu statues smashed and decapitated, walls and monumental gates flattened—centuries of history deliberately erased. Reliefs and sculptures that had survived nearly 3,000 years were shattered into pieces, a stark reminder of how fragile our connection to the past can be.

Khorsabad, or Dur-Sharrukin, fared slightly better. Built by Sargon II as a purpose-built capital, its palace foundations, city walls, and lamassu guardians mostly survived. Some statues and smaller architectural features were damaged or looted, but the city’s overall layout and grand scale remain intact, giving us a glimpse of its original glory. Thanks to earlier excavations and documentation, heritage teams were able to step in and protect much of what remained.

Mosul

Mosul, the city where ISIS established its caliphate, may have been the most damaged city and is one of the original sites ISIS tried to destroy. They destroyed a Mosque Dedicated to Prophet Jonas, Al-Nuri Mosque (ironically, the place where they declared the ISIS caliphate), Mosul Museum which housed important relics and artifacts from Ninevah and Hatra, Mosul library, many Churches and many more cultural and religious institutions.

The damage in Mosul is hard to describe – and while local and international NGO’s have done a fantastic job at reconstructing many of these places, the scars in Mosul are still visible. The old city is a harrowing reminder of the damage ISIS did against ordinary people.

Why Did ISIS Choose Historical Sites?

There are many reasons why ISIS chose historical sites:

- To cause terror and conversation: Terror of course was the main priority of ISIS and by live-streaming the sites ISIS tried to destroy, massacres, attacks on religious places, they were gaining the attention of the world. While causing terror, they also used these incidents as a way to recruit new members from overseas

- Ideological Motivation: ISIS believed that monuments and historical sites from empires of any religion (including Islam) were idolatrous or “pagan”. Therefore, in their eyes, they needed to be destroyed.

- Looting: While they destroyed many historical sites, the policy of destroy what you can’t carry was rife. Many priceless artifacts that belong to Iraq and Syria were smuggled out and sold illegally to help fund ISIS ventures.

- A Place To Hide: ISIS lacked aerial protection – so they began training grounds in places such as Hatra as they knew governments would not attack such key historical sites. They were able to use these historical sites to their advantage to set up camp, hide weapons and train. Beyond being sites ISIS tried to destroy, they also used these sites as protection.

Other Types Of Destruction By ISIS

There were many other massacres committed by ISIS. The Camp Speicher massacre in Tikrit, The Sinjar Massacre, massacres of the Sheitat Tribe in Der ez-Zor, and the victims of the Tal Afar massacre are just some of the most tragic examples of such.

Besides the physical damage, there is another layer of almost irreversible damage they attributed to: a global misunderstanding of Iraqis and Syrians, as well as Islam. Unlike other terrorist groups, ISIS openly welcomed foreign fighters to join the cause. As of December 2015, approximately 30,000 fighters from at least 85 countries flocked to Syria and Iraq to join the fight.

While ISIS is often portrayed as a Muslim group (and claim to be), it is estimated that 85% of victims of ISIS attacks are muslim – Sunni, Shia and other sects also. The remaining percentage were Yazidis, Christians and other minorities who were targeted first.

Rebuilding Sites ISIS Tried To Destroy

As mentioned previously, many sites such as Hatra and Al Nuri mosque have undergone renovations to try to repaid the damage ISIS did. Many of the sites ISIS tried to destroy can be visited, with many locals looking forward to the days where visitors will return in the amount they did before ISIS ever declared their caliphate.