Occupying 500,000 square miles and stretching across huge chunks of both Mongolia and China, the Gobi Desert is second only to Arabia for deserts in Asia. It stretches from Mongolian planes and the foot of the Pamir mountains to the edges of Manchuria and the Himalayas. Vast tracts of bare rock and sandy planes provide little escape from the scorching heat of the sun or the bone-chilling freeze of the night. It’s one of the great natural wonders of Asia, rich in culture and history, having formed a major part of the ancient Silk Road, hosted parts of the Great Wall of China and having a large number of startlingly well preserved fossils.

To be frank, this is a big topic. One we’ve covered before, albeit less extensively. Many people would begin and end at it being a massive chunk of empty nothing squatting in the middle of Asia. That’s not good enough for me. This is going to be the complete guide to the Gobi desert. So let’s get started!

Geography of the Gobi Desert

If you’re like me, Geography class in school completely bored you to tears. All the same, we’re gonna have to address it if we want to understand the Gobi desert, so I’ll try not to make you too bored. Even worse, we’re gonna have to divide this into sub-sections because it’s an enormous topic in its own right. First of all, let’s talk about the area.

Area

Like I said, the complete area of the Gobi desert is 500,000 square miles, but the desert itself is very much not a square. From its furthest tip at the south-west to the furthest tip of the north-east, the distance is about 1000 miles total. What spans the desert is cut off by a few distinct spots. In the north, it’s stopped by the Altai mountains and the Mongolian steppe, a point at which describing the landscape as ‘desert’ becomes less accurate. To the west, it merges into the Taklamakan Desert in Xinjiang, China, with landscape and conditions changing to the point that describing it as the same desert would be inaccurate. In the southwest it is cut off by the Tibetan plateau in the Himalayas and what’s known as the ‘Hexi Corridor’, a vast expanse of interspersed oases. Lastly, it merges into the North China plains in the south-east, effectively locking the desert in from there.

Ecoregions of the Gobi Desert

The Gobi Desert can be broadly divided into five ecoregions, varied by differing climate and topography. Firstly there’s the Eastern Gobi desert steppe, covering the Inner Mongolian plateau in China and the Yin mountains. It is bound by the Mongolian-Manchurian grassland, the Yellow river and the Alashan plateau. Secondly the Alashan plateau semi-desert consists of desert basins and low mountains between the Gobi Altai range, the Helan mountains, the Qilian mountains and the Tibetan plateau. The Gobi Lakes Valley desert steppe comes third, lying north of the Alashan plateau, between the Gobi Altai range and the Khangai mountains. The Dzungarian Basin semi-desert comes fourth, covering portions of Xinjiang province and extending into south-eastern Mongolia, as well as being barred by the Emin Valley steppe on the China-Kazakhstan border. At last, there’s the Tian Shan range which separates the desert from the separate Taklamakan desert.

Climate

The climate of the Gobi Desert is pretty damn harsh. On the whole, it’s a cold desert, going so far as having snow and frost on its dunes every now and then. Being elevated between 3-5 thousand feet above sea level and located so far to the north, the temperature is naturally rather harsh. Even worse is its prime positioning for cold winds rolling in from Siberia, often bringing snow in its wake. This tends to be the bulk of precipitation in the desert, given its average 194 millimetres of rain per year, just barely enough for the hardiest of desert plants.

With all of this combined, the average temperature during the winter is a brutal -21 degrees celsius. While in the summer, it rises as high as 27 degrees celsius at maximum, sometimes managing to spike far higher to over 40 degrees celsius Or far lower in the winter, to under -40 degrees celsius. Cruellest of all is how quick the changes can be. Deserts like this aren’t particularly consistent, with a 35 degree shift being recorded in under 24 hours.

Geology

The Gobi desert is not particularly sandy. Sure, there’s a lot of sand around, but you’re not going to see quite so many massive sand-dunes as in Arabia or the likes. The bulk of the desert actually consists of wide basins with smooth, rocky floors dusted with sand, clay, pebbles and gravel. Estimates suggest that only about 10% of the desert primarily consist of outright sand dunes, a far cry from the deserts of Arabia or the likes of the Sahara in Africa.

Much of the sediment existing in the desert is believed to have come from the Altai mountains, the Heihe river and the southern Mongolian highlands, having been transported intermittently by floods over many millions of years. This differs somewhat from other deserts that formed from much more consistent ocean levels receding and leaving behind a long-eroded bed of silt, which forms the sand dunes. Granted with the time-scale we’re talking of, the Gobi desert could have been flooded for hundreds or even thousands of years at a time without making the same kind of dent, so don’t get the wrong idea of these ‘intermittent floods.’

Even with how utterly boring it is talking about rocks knocking about a big empty plain of sweet Fred Astaire, there is one interesting snippet that caught my eye: The Gobi desert is typically surrounded by cliffs. If one is to look at these cliff sides in certain areas, one can see quite clearly where the ancient ocean levels used to lie. It’s true! You can see a ‘lip’ on some of them, demonstrating the coastline where the most violent ocean waves would have taken a harsher toll on the rock. Even more, by looking further down and looking for odd lines of discolouration, you can (if you understand geology better than I do) predict a lot about the environment of the era the lines were formed in. The colour is typically influenced by the type of sediment in the water, as well as the climate of the time! …I found it interesting anyways.

Notable Fixtures

It would be unfair to characterise the desert as a mass expanse of nothing. As I have been doing. Right up until now. But anyway, there actually are a wide number of spots in the desert that are more worthy of consideration.

First we have the Valley of the Lakes. This is a 500km long and 100km wide valley that has a number of large saline lakes. Due to being salty as hell, they aren’t of huge use to the animals and few people living around there, but with purification technology, it’s entirely possible to gather potable water from one of the many lakes so that you don’t… Y’know, die of thirst in the harsh desert environment.

The ‘Flaming Cliffs’ are another iconic site in the desert, located at the Djadochta Formation. So-called because of the bright red colour of the sandstone in the desert sun, the Flaming Cliffs are most notable as an archaeological site. Velociraptor fossils have been found and perhaps most interestingly, this served as the first known location of dinosaur eggs. Historically, the region is extremely important.

The ‘Green Great Wall’ is an interesting human-caused fixture of the region. A problem with the Gobi desert is that it’s, well… Expanding. As it encroaches ever further onto Chinese farmland, the people have grown increasingly concerned, leading to the 1978 ‘Great Green Wall’ program. While not expected to be finished until 2050, the Green Great Wall is intended to act as a large natural windbreaking barrier, preventing soil erosion and preserving the land from further harm which has destroyed up to 3,600 square kilometres of grassland every year. When finished, it’s hoped that north China’s forest coverage will grow from 5 to 15%.

The Khongoryn Els is another fascinating spot, lying within the Gobi Gurvansaikhan National Park in Mongolia. Most notable for being one of the few spots in the desert with proper sand dunes, which it delivers on with great overcompensation. The dunes are spread out over 965 square kilometres and can reach individual heights of over eighty meters, comparable to sand dunes in Egypt. What makes the site particularly unique is its nickname ‘the Singing Sands’, so called because of a unique, only partly explained phenomenon where the shifting of these sand dunes produces a distinctive noise. The sound has been compared to an aircraft during landing and takeoff.

Life in the Gobi Desert

At last we can stop talking about rocks. Despite deserts popularly being known as vast expanses of nothing, life still exists in great abundance! It’s time to go over what life does call the Gobi desert its home, from plants and animals to humans!

Flora

Deserts are pretty inhospitable places, so it’s fair to say that plants don’t have an easy time there. Unlike some of the deserts in America, the Gobi desert doesn’t even have an abundance of cacti. Rather, we can round it down to some five key plants that have made the desert their home. Or at least parts of it. You’re still going to find yet more miles upon miles of absolutely nothing in plenty of places.

Starting with the Saxaul, we get the desert’s only consistent tree. A tiny little weatherbeaten thing with branches twisted by the harsh winds, pushing it into often strange shapes. If one wonders why such a thing is able to grow there, you only need to start hacking it apart. Unlike a lot of trees, the bark itself is a heavy water-storer. Tightly packing bark together is a (very poor) way of gathering water.

Wild onions also grow in the region, as one of the few sources of natural non-animal sustenance for the nomadic folks that travel through the desert. A type of bindweed called ‘convolvulus ammonia’ is a rare flowering plant in the desert, featuring small white flowers. Yet another plant is the saltwort, a curiously hardy small green plant, almost a shrub, that thrives on areas of high salt content. The plant is dreadful for eating due to the sheer salt content of it. Lastly, for our purposes at least, we have the sophora, an evergreen flowering plant with roots that have proved useful for traditional Chinese medicine. The plant has anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, making it suitable for use to treat heart disease. I wouldn’t recommend it as an alternative to proper medicine, more just a helpful addition.

Fauna

Some hardy animals would call the Gobi desert their home. A surprising variety as a matter of fact! Estimates suggest 49 mammals, 15 reptiles, an amphibian species and over 160 varieties of birds live within the desert, many of which are exclusive to the region and extremely rare. From the tiny hopping desert-mouse known as the jerboa to massive Gobi bears, they range in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Though they may not be that easy to spot.

There’s a few key species worth elaborating on. Starting off, the wild Bactrian camel. What’s pretty unique about this is that these are the only known wild camel species in the world! This differs from feral camels, the likes of which can be found even in non-native habitats like Australia, which are descended from long-domesticated camels. This species has never been domesticated, no doubt owing to their extremely limited range within the desert. Due to hunting and territorial encroachment, the species is estimated at a mere 1,400 remaining individuals. It may not be long before all that remains are domesticated camels.

The golden eagle is naturally a fixture. What with the Gobi desert being in Mongolia and all, there’s a long historical link between the eagles and the nomadic inhabitants of Mongolia, where falconry has been a long and storied tradition. Golden eagles are a mark of experience for falconers due to their immense size and tendency towards aggressiveness. It takes someone far more experienced to take one on as a partner, so you can bet that any nomad with a golden eagle by their side is someone very impressive indeed.

The aforementioned Gobi bear is an especially unique species. With only thirty known individuals remaining in the wild, it’s the rarest bear species in the world. They’re a rather herbivorous species, mostly subsisting on roots, berries and the few other plants existing in the desert, only occasionally feasting on some of the rodent species and with very little evidence of hunting much else. It’s unfortunately quite likely that within another decade or two, this species may become considered entirely extinct in the wild.

As well as various types of gazelles, a few snakes and the curious marbled polecat, there’s one remaining species that deserves mention. The beautiful snow leopard, top apex predator in the desert and one of the most illusive species of wild cat in the world. Despite a (relatively) solid population of around 10,000 across the world, ranging through Siberia, Central Asia, Afghanistan, India and China, the snow leopard mostly inhabits the hardest to reach regions of the world and spread themselves sparsely. The famous Planet Earth documentary by David Attenborough highlighted how difficult to capture and rare footage of the species is.

People

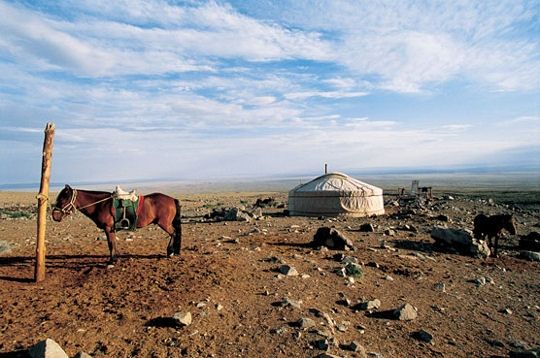

Just because it’s a desert, that doesn’t mean it’s completely devoid of human life! I wouldn’t quite say it’s the contrary, but people do indeed live there. With a rough estimate of three per square mile (no doubt far more clustered than consistent with that), nomadic folks still do call the region their home. Nomadic really is the key word, since such an inhospitable climate and landscape requires one to stay on the mood. One spot that has the necessities for survival may only last you a short while, something that fits into the traditional Mongolian way of life.

Mongolia in general has a large nomadic culture. Even now, around a quarter of the population is to some degree nomadic, albeit mostly along the Mongolian plains and steppes, not so much the harsh environment of the Gobi. Those that do persist there have a fusion of traditional and modern culture. On the one hand, animal herding, falconry and Ger tents. On the other, solar panels and motorbikes.

Surprisingly, there are in fact small towns existing within the Gobi desert, primarily in Mongolia proper. The Dornogovi Province and SouthGobi Province have populations between 60,000 and 70,000 each and comprise the bulk of human activity within the desert. Even still, in most cases, the individual towns have fewer people than there are square kilometres in the area.

Dornogovi itself has fourteen distinct towns, with the largest, Sainshand, having a mere 20,000 inhabitants as of 2009, a density of 8.74 people per square kilometre. This still makes it by far the most densely populated region, with every other subdivision having well under one person per square kilometre, with the exception of Zamyn-Üüd, which screws up my point slightly by having 26.34 people per square kilometre. Still, this area is only 486.80 kilometres to begin with, so I’d hardly say it counts. SouthGobi province meanwhile is even less inhabited. With its 15 subdivisions, the largest, the regional capital of Dalanzadgad has a mere 12,000 inhabitants within its 476 kilometre area.

History of the Gobi Desert

Believe it or not, even a desert can have a whole lot of history to it. From its formation over millions of years to its human history, the Gobi Desert has experienced a lot and been a huge part of a lot. We might as well have a deep-dive into some of that.

Pre-History

Of course we could really go back indefinitely with this. The land that makes up the Gobi desert was at one point the cosmic debris that floated about the universe in pre-Earth times. God knows exactly how any of that came to be. Perhaps literally, but let’s not turn this into a theological matter. Anyways, the earliest thing that it seems can be agreed upon is that the arid climate that characterised the region began around 50 Ma. (Ma is a geology term, describing years past in the millions. 50 Ma is 50 million years ago, as opposed to assigning a BC date.)

The collision of tectonic plates and the growth of the Himalayas in this period is what contributed to the blocking of water vapour, thus causing desertification. This process was, of course, incredibly slow and the modern landscape was only eventually developed by 2.6 Ma, with different events in different regions being charted by estimated ages of silt. Silt at the Xorkol basin in the Northeastern Tibetan plateau has dated as far back as 51 Ma while silt in the Tajik Basin are 39 Ma. Some estimates even put the Badain Jaran desert (part of the Gobi desert) at a mere 1.1 Ma, though this is still quite controversial. The full formation of the desert took many millions of years and as judged by the more recent desertification, is an ongoing process.

Some of this silt has been determined as the result of wind-weathering or the violence of shifting tectonic plates. Others are likely the result of the no-longer existing Paratethys ocean, which at one point flooded large parts of the Gobi desert region before receding between 40 to 30 Ma. Subsequent periods saw infrequent flooding and formings of other seas which may have lasted for thousands of years each, but which barely appear as a blip on the historical radar when looking back this long. The regionalism of much of this does a lot to explain the diversity of the landscape in the Gobi desert.

Human History

Okay, so all that pre-history stuff is pretty confusing and vague, but it gives you a rough idea of how the Gobi desert became what it is, right? It’s the human history that’s most interesting. It’s not like human civilisation just had to work around the desert, it was something people had to live with. And sure enough, it sat right between Mongolia and China, two of the towering imperial powers of the ancient world!

Written history of the Gobi desert seems to be quite hard to come by. Most accounts start referring to the desert in the time of Marco Polo, so we’re talking the latter half of the 13th century. Marco Polo described it being so long that it would take a year to travel from end-to-end and at least a month at its narrowest point. Despite this, Marco Polo already describes trade routes through the desert being well established by this stage. Hardly surprising since at this time, the Mongol Empire held control of China under Kublai Khan. The empire was in a period of turmoil and disintegration by this time, but such trade routes absolutely existed.

Perhaps the earliest evidence of human activity in the desert is rather recently discovered. In 2012, evidence surfaced of remnants of an unknown portion of the Great Wall of China which extended partially into Mongolia proper. Up until this point, the belief was that while the great wall extended through the adjacent Ordos desert in China, it never moved into the Gobi. Radiocarbon dating of portions of the wall estimate that construction occurred between the early 11th and late 12th centuries, consistent with the Great Wall. While it is currently not proven, it certainly makes a compelling case.

From these periods onwards, the Gobi desert served as part of the Silk Road trade route, connecting Mongolia with China and thus with the rest of the world for trading, prompting some permanent settlements around the few oasis to supply such journeys. This later led to European exploration of the region in the late 17th century, gradually expanding until an explosion of activity in the late 19th century, no-doubt as a result of European military incursion into China. Exploration later continued under the Chinese, Mongolian and Soviet governments before spiking once more in the 1990s when major fossil finds were recorded in the region. Given the release of films like Jurassic Park at the time, it’s hardly surprising that this would prompt such a boom.

One last curious historical anecdote is an incident of an American weather station based in the Gobi desert being caught in the Japanese invasion of China. Seeking the aid of local Mongols and the Sino-American Cooperative Organisation, the Americans hijacked a Chinese junker and sailed to Okinawa. (The Sino-American Cooperative Organisation was a Chinese intelligence operation working jointly with the US. It was led by the head of then Chinese leader Chiang Kai-Shek’s secret police, Dai Li. Which anyone who watched the Avatar TV show may recognise.) The story was later exaggerated and turned into a movie, Destination Gobi.

So… That’s it! That’s our complete guide to the Gobi desert! Well, perhaps this has made you want to visit. Certainly, you can book yourself a trip there and go exploring if you’re a seasoned adventurer. As for us, we at least grace part of the Gobi desert as part of our Mongolia Naadam Festival tour! You should check it out!