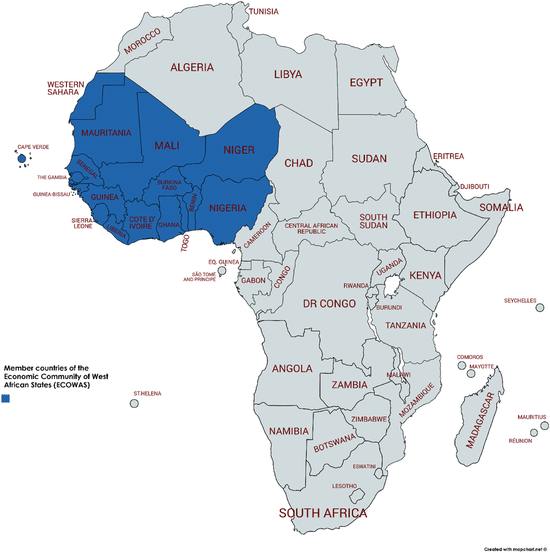

If you have spent any time in West Africa, you have probably heard of ECOWAS, the Economic Community of West African States. On paper, it is a regional powerhouse, created in 1975 by fifteen countries to promote trade, cooperation, and political stability. In reality, it is a bureaucratic nightmare, a mix of ambition and dysfunction, and the organisation is constantly tested whenever revolutionary governments rise up and shake the foundations of nations.

Table of Contents

The Purpose and History of ECOWAS

ECOWAS was born from the optimism of post-independence leaders who wanted West African countries to work together. The idea was straightforward. If nations trade more, coordinate policies, and resolve disputes peacefully, everyone benefits. The organisation has achieved some remarkable successes. It helped mediate conflicts in Liberia and Sierra Leone, provided a platform to oversee elections in Côte d’Ivoire, and occasionally deployed peacekeeping forces to prevent full-scale civil war.

But for every success, there is a spectacular failure. ECOWAS relies on diplomacy, negotiation, and the threat of sanctions. These tools are only effective if governments care about regional opinion. Revolutionary regimes often do not, and the last few years have made this painfully clear.

Revolutionary Governments and ECOWAS’ Limits

The recent spate of coups and revolutionary governments across West Africa illustrates the limits of ECOWAS authority. Burkina Faso, Mali, Guinea, and Niger have all seen military or revolutionary takeovers in the last five years. These governments typically justify their actions as a response to corruption, incompetence, and the failure of previous administrations to provide security or economic opportunity.

Take Burkina Faso. In 2022, President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré was ousted amid rising public frustration and ongoing jihadist attacks. The military stepped in, first under Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba and then Captain Ibrahim Traoré. These leaders style themselves as revolutionary figures, promising to reclaim sovereignty from foreign influence and restore national pride. ECOWAS reacted with threats of sanctions, border closures, and diplomatic pressure. The revolutionary government did not flinch. The population, exhausted by years of instability and disillusioned by the previous regime, largely supported the new leadership. In practical terms, ECOWAS’ tools were useless.

Mali tells a similar story. In 2020, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita was removed by the military amid protests over corruption and insecurity. A transitional government promised reform, but the cycle repeated with another coup in 2021, leaving Colonel Assimi Goïta in power. ECOWAS imposed sanctions and suspended Mali from regional bodies, but Goïta’s government remained firmly in control. Revolutionary leaders exploit ECOWAS’ reliance on diplomacy by presenting sanctions as interference by distant elites.

Guinea and Niger offer the same lesson. In 2021, Alpha Condé was removed in Guinea by Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, justified by corruption and mismanagement. In Niger, a coup ousted President Mohamed Bazoum in 2023, leaving ECOWAS scrambling to enforce sanctions and mediation protocols. Revolutionary governments across the region operate on populist legitimacy, military backing, and the promise of autonomy, making ECOWAS’ traditional tools feel outdated and impotent.

Security, Sovereignty, and Populist Legitimacy

Part of ECOWAS’ struggle comes from the deep insecurity these revolutionary governments claim to address. Jihadist groups and local militias operate across the Sahel, exploiting weak states. Revolutionary leaders position themselves as the only ones capable of confronting these threats, unencumbered by foreign influence or bureaucratic procedures. ECOWAS, by contrast, is a slow-moving regional organisation, reliant on consensus and negotiation. Military decisiveness and populist legitimacy often outweigh diplomacy.

The issue of sovereignty is central. Many revolutionary governments reject foreign presence, particularly French influence, which ECOWAS is perceived to support. Leaders in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Guinea frame ECOWAS not as a regional protector but as an extension of the old colonial order. Populations often agree, especially in rural areas where foreign involvement is associated with past failures and exploitation. ECOWAS’ credibility suffers as it appears aligned with interests that revolutionary governments and citizens reject.

The Challenge of Fragmented Politics

West Africa is politically fragmented. Revolutionary governments highlight the weakness of existing institutions and the inability of prior leaders to deliver security or prosperity. ECOWAS faces the impossible task of enforcing unity in a region where legitimacy is constantly contested. The organisation has been effective in mediation when governments are willing to cooperate, but revolutionary regimes operate outside those norms. They consolidate power locally, often defying both national constitutions and regional expectations.

Sanctions, border closures, and diplomatic pressure only go so far. In some cases, they strengthen the revolutionary narrative, painting ECOWAS as a tool of elites rather than a neutral arbiter. Revolutionary governments survive by exploiting this dynamic, appealing directly to citizens’ frustrations and demonstrating that regional opinion is secondary to domestic authority.

ECOWAS’ Role Today

Despite these challenges, ECOWAS is not irrelevant. Its very existence forces revolutionary governments to consider regional consequences, even if reluctantly. It provides a platform for dialogue, which sometimes prevents conflicts between neighbours from escalating into full-scale war. ECOWAS’ presence also matters for international aid coordination, economic agreements, and the monitoring of elections. While slow and often ineffective, it remains a stabilizing factor in a turbulent region.

ECOWAS’ failures also illustrate a larger truth about West Africa. Revolutionary governments are a response to decades of corruption, poor governance, and insecurity. They challenge not only domestic elites but also regional authority and foreign influence. Understanding ECOWAS is key to understanding why coups continue to occur and why revolutionary leaders persist.

Conclusion

ECOWAS is a mix of ambition and dysfunction, a regional body striving to enforce order in a chaotic political landscape. Revolutionary governments in Burkina Faso, Mali, Guinea, and Niger expose the limits of its authority. Military-backed, populist regimes reject sanctions, border closures, and diplomacy, consolidating power locally and challenging the legitimacy of regional oversight. Security crises, foreign intervention, and the promise of revolutionary change make ECOWAS’ role precarious.

For anyone trying to understand West African politics, the lesson is simple. ECOWAS exists, it matters, but revolutionary governments show the limits of its influence. These regimes will continue to challenge regional norms, and ECOWAS will struggle to respond effectively. The organisation’s history of successes and failures offers insights into the complicated, messy, and unpredictable nature of West African politics. In a region defined by rapid change, insurgency, and populism, ECOWAS remains a symbol of ambition and the persistent tension between ideals and reality.

Click to check our West Africa Tours.