If there was ever a place name synonymous with war, it would be Stalingrad. It’s very rarely discussed outside the context of the battle waged there, what many call the turning point of WW2 where Nazi Germany went from unstoppable juggernaut to meat in the Soviet grinder. And there’s a good reason for that, of course Stalingrad would be remembered for those things! But here, we’re going to take a different approach and look at Stalingrad on its own terms. Oh, don’t worry, we’ll be looking at the battle itself in the future, but to keep this from being too long, it’ll be glossed over a little here. In any case, let’s get started!

Ancient Stalingrad

Given the city’s location on the west-bank of the Volga (hence its other name, Volgograd), the area around this city was always attractive to human settlers. The earliest (known) settlement is the paleolithic (80-100 thousand years ago) ‘Dry Mosque‘ site by the banks of a river of the same name that leads to the Volga. Discovered in 1951, this is one of the most explored sites of its era in Russia and showed evidence of a small settlement of 35-40 people with even evidence of rudimentary homes. If you want to point to the origin of Stalingrad, this may be the furthest back you’re gonna get.

The region stayed important historically, intersecting with important trade routes between Asia and Europe. It’s known that in the 13th and 14th century, the region was controlled by Mongol Golden Horde, with an unknown city sitting right on top of Stalingrad, commonly known as the ‘Mechetnoye settlement‘, evidenced with a few ruins and coins from 1274 to 1377. Alas, most of the ruins were destroyed in the Russian construction of the city centuries later. By the 15th century, the Golden Horde began to crumble and collapse while a new authority in Moscow expanded its reach.

Tsaritsyn

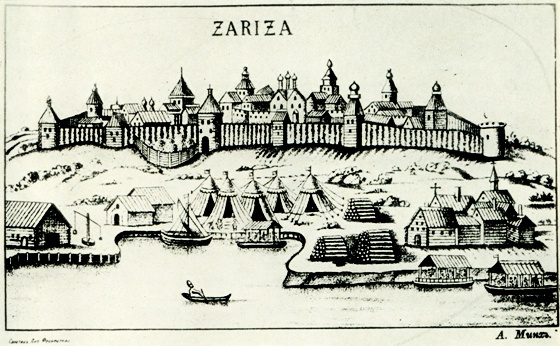

The evidence for when Russian forces first moved into the region has been lost to time, though we know from at least 1579, an English traveller had noted in the area an island called Tsaritsyn and that a detachment of 50 archers were placed there to keep the roads clear for trade. Not so much a settlement as a fort, but now we have the first Russian name. ‘Tsaritsyn’. Under the rule of Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich in 1589, on July 2nd, an order was made to establish a city and a prison on the location, which was officially noted as being Tsaritsyn by 1600.

It should be noted, the word ‘Tsaritsyn’, despite its name, doesn’t come from the Russian Tsar. It’s believed to come from a similar Turkic word which translates to ‘yellow, muddy water’ and is often just a term for ‘river’ in Kazakhstan. The region certainly still felt that influence, with regular raids from the remnants of the Golden Horde killing people and taking others into slavery. The right bank of the Volga river was considered ‘Crimean’ for many years due to the raids from the Crimean Khanate located not far away.

Throughout the late 1600s and early 1700s, Tsaritsyn is seized several times in various revolts, only to be recaptured by the Tsar’s forces. It was simply too important a trade route to fall, but that same importance made it a constant target. During the 1773-1775 Pugachev rebellion, every settlement in the region fell to the uprising except for Tsaritsyn, which saw the deciding battle of the conflict and victory of the Tsar once again. In recognition of this success and the relative stability of the city, it began to see much greater investment in development form the government.

Tsaritsyn became a valuable producer region, hosting large fields, factories and places of education that weren’t common in the region. It became connected to yet more of Russia by railway in the mid-1800s and by 1913, had grown to a city of over 130,000 people. It was the most industrially capable in the region and naturally, with developed industry comes the growth of the proletariat class. As WW1 dragged on, the presence of that class became very important indeed.

The Bolshevik Revolution

On the 27th of November 1917, Tsaritsyn fell to the Bolshevik forces in the heat of the revolution, becoming a significant power-base in southern Russia. In July of 1918, the Soviets were tested for the first time by the royalist Great Don Army who assaulted the city, attempting to retake it. Leon Trotsky appointed the Bolshevik military leaders to head the defence of the city, though at around the same time, Joseph Stalin was also sent to Tsaritsyn to handle grain procurement of the sizeable farmland around the city. Stalin clashed with Trotsky’s appointed military leaders and interfered in their strategies.

Trotsky was in favour of using experienced military leaders who once fought for the Tsar as the backbone of the defence, while Stalin believed that such forces couldn’t be trusted. This wasn’t an uncommon opinion, the attitude among many Bolsheviks was that class antagonisms made their interests largely separate. The thing is, Stalin wasn’t even entirely wrong! Former Tsarist military leader Andrei Snesarev was openly derisory of the Bolsheviks and his conduct in battle was unimpressive. Stalin was able to get him recalled and began taking over the defence of Tsaritsyn himself.

Stalin faced major pushback within the Bolsheviks and at first, he was recalled to Moscow in September over the high casualty rates among the defending forces. Stalin later returned, defied the new orders he’d been given but successfully managed to route the anti-communist forces and raise his prestige once more. On October 19th, he was recalled to Moscow again, only for a renewed offensive against the city to begin at the start of 1919, ending with the city falling in June. The Red Army successfully retook it for good in January 1920.

As the civil war raged on, 1921 saw the start of the Volga famine, a terrible cocktail of natural poor weather, the chaos of civil war and deliberate Soviet grain seizure policies that caused mass starvation and terrible death in the region right until 1923, when the wrapping up of the civil war allowed a return to normalcy. An uncertain normalcy, but normalcy all the same, a time for rebuilding and renewal.

Stalingrad

On the 10th of April 1925, in recognition of his unexpected successes during the siege of Tsaritsyn, the city was renamed to Stalingrad, with the neighbouring Tsaritsa river renamed to Pionerka as well. While the city wasn’t named after the Tsar, as we’ve discussed, it’s pretty obviously going to be on people’s minds after the Tsar was shot dead by revolutionaries. The place needed renaming and naming it after the ‘war hero’ who’d defended it seemed appropriate. This naturally raises eyebrows as everyone knows of Stalin’s infamous cult of personality, though he hardly started the trend. In 1923, the city of Gatchina was renamed Trotsk after Leon Trotsky. Saint Petersburg became Leningrad in 1924. Many more cases followed.

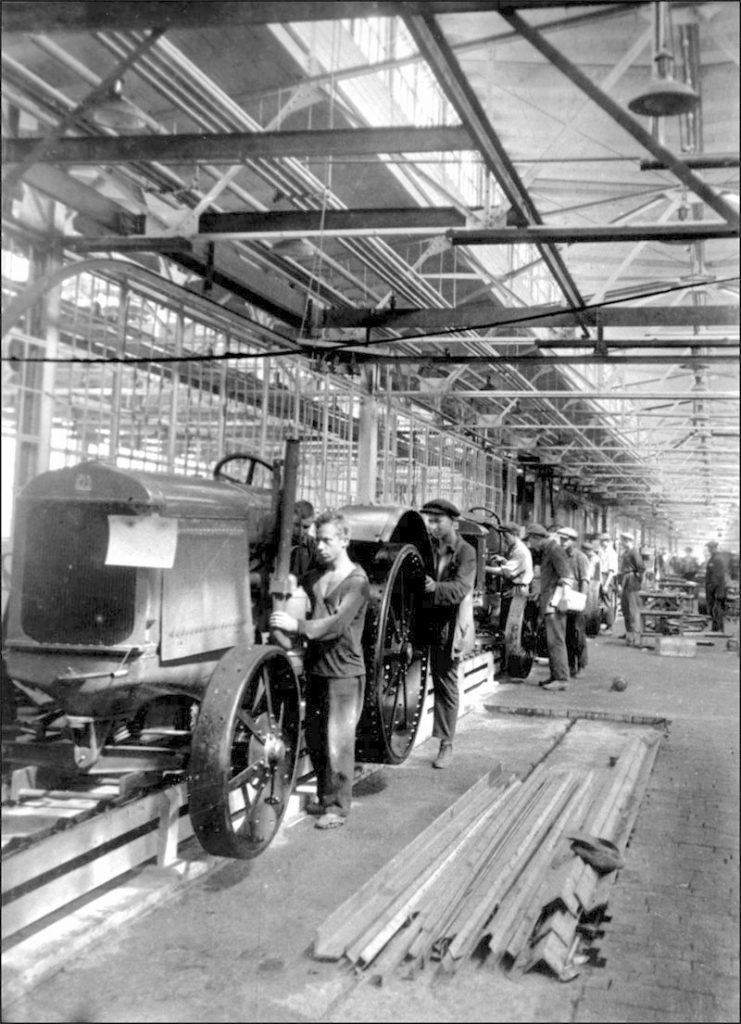

The city once again began an industrial boom during peacetime, with factories for farm machinery and armaments becoming significant in the city. The Stalingrad tractor factory in particular was highly advanced, hosting the first automated machine tool line in the USSR by 1939. By that point, more than a quarter of a million tractors had been produced, making it a beating heart of the regional economy and agricultural scene. The Soviet economy was booming and seemed set to continue to boom! …But that didn’t last for too long.

Nazi Germany invaded. The chaotic campaign across the eastern front say the deaths of tens of millions of Soviet citizens, with German troops coming within eyesight of Moscow. There was seemingly nothing that could stop them until once more, forces came to the walls of the city. Stalingrad was an important industrial centre, but more than that, it was a crown jewel for Hitler to seize. The propaganda value was enormous and both sides recognised it, throwing their efforts behind the effort into what became one of the largest battles in history.

The details of the battle of Stalingrad deserve their own article. Which they will have! But for now, all that needs to be known is that on the 17th of July, 1942, the battle began and on the 2nd of February 1943, the battle was over. With somewhere in the region of two million lives lost, split roughly evenly between the sides. The city had been smashed to pieces and the Nazis simply couldn’t recover their losses. The defeat marked the first in a string of steady defeats that pushed the Nazis all the way back to Berlin and put an end to the fascist government for good.

After the Battle of Stalingrad

On the 1st of May 1945, Stalin bestowed the title of Hero City to Stalingrad in honour of its supreme sacrifice to the war effort. The city was practically rubble, as was much of the rest of the country, but rebuilding had to begin! It was an uneasy process at first. By the end of the war, two years after the end of the battle, housing in the city was at 37.4% of pre-war levels. Many thousands lived in dugouts. By December of 1949, it was reported that Stalingrad’s industrial capacity exceeded its pre-war levels by 31.5%, no-doubt aided by the massive payments of reparations from partitioned Germany, as well as the labouring of German POW’s.

Development continued in the 1950s. Transport infrastructure continued to grow and new technological developments were applied, like the construction of what was at the time, the largest hydroelectric dam in Europe. Stalingrad remained one of the most advanced cities in the USSR. But behind the scenes, things were changing. Stalin himself died in 1953 and a power struggle was occurring within the USSR, one which was ultimately won by Nikita Khrushchev who began a policy of de-Stalinization.

On November 10th, 1961, the city was renamed to Volgograd as part of this policy. Despite this, the moniker of Stalingrad remained for many, with all references to the war particularly knowing it as Stalingrad. Despite the de-Stalinization efforts, the blood of a million Soviets had been spilled to defend the city and perhaps for that reason, it was kept out of the political ‘games’ and awards to defenders of the city continued to know it as Stalingrad.

The 60s and 70s focused on continual economic development. Architecture began to change as Khrushchev repudiated the old ‘Stalinist’ architecture in favour of blocky, easy to manufacture buildings often called Khrushchyovka. Cities that had been particularly damaged by the war effort saw an especially large amount of these. Development began stagnating under new Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and aside from some notable cultural creations like museums to the battle of Stalingrad, the historically breakneck economic development had finally stunted.

Collapse of the USSR

With Brezhnev’s death and the eventual rise of Gorbachev to Soviet leader, the Soviet economy had stagnated for a while. Things were at least stable, but Gorbachev had new ideas to boost the economy… Capitalist ideas. The perestroika (restructuring) reforms of the mid-late 80s saw a rapid economic decline and rising unrest. Throughout the late 80s, socialist countries began reforming into capitalism or simply outright collapsing. By the start of the 90s, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union had lost authority to the right-wing organized around Boris Yeltsin. In 1991, the USSR was dissolved and the Russian Federation took over.

Construction projects in former Stalingrad were halted as the state organs administering them ceased to exist, authority passed on to new oligarchs and private investors who had little interest in many of the new buildings and public utilities. Many half-constructed buildings remained that way for years and even decades, some even remaining this way. Poverty exploded throughout the city and from 1996 to the early 2010s, the city became an infrequent target for Islamic terrorism owing to its closeness to the Caucasus region, where Muslims in the likes of Chechnya were fighting for independence from Russia.

Since the collapse of the USSR, there’s been a lot of contention over the city’s name. A renewed monarchist movement have called for the renaming of the city to Tsaritsyn, despite the name’s connection to the Tsar being purely coincidental. Separately, there’s been a push to rename the city back to Stalingrad, an idea that has significant support among some sectors of the population, though the Russian government hasn’t particularly pushed for such a change.

That about sums up the history of the city of Stalingrad! Y’know, discounting that massive war that will probably get an article even longer than this one down the line. Hopefully you’ve learned a few things! Even more hopefully, perhaps you’ll be willing to visit it some time and drink in some of that history yourself!