How three adaptations of Mutiny on the Bounty tell the same story differently

Few historical events have been refracted through Hollywood as thoroughly as the mutiny aboard HMS Bounty. The story has been revisited across three major Hollywood studio adaptations (or five if one counts the lost 1916 Australian silent film The Mutiny of the Bounty, directed by Raymond Longford and starring George Cross as Bligh and Wilton Power as Fletcher Christian, of which only a handful of stills survive, as well as the 1933 semi-documentary In the Wake of the Bounty, which featured Errol Flynn in his first on screen role, portraying Fletcher Christian in dramatized reenactments). However, the same basic facts are reshaped to reflect radically different ideas about Captain Bligh’s authority and the ensuing rebellion led by Fletcher Christian. What changes most from film to film is not just tone or performance style, but why Fletcher Christian and his followers mutiny and what that mutiny means.

Below is a look at and comparison of all three film adaptations of Mutiny on the Bounty:

Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)

- Release year: 1935

- Director: Frank Lloyd

- Stars: Charles Laughton, Clark Gable, Franchot Tone

- Studio: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

- Runtime: 132 minutes

- Academy Awards: Best Picture (1936)

The 1935 version establishes the template for the other two adaptations which followed in 1962 and 1984. This is a big studio epic where the mutiny on the Bounty is framed squarely as Fletcher Christian’s moral response to Captain Bligh’s tyranny. Charles Laughton plays Bligh as a sadistic martinet, reveling in cruelty, humiliation, and punishment. Clark Gable as master’s mate Fletcher Christian portrays a man pushed to the edge, with mutiny presented as a last resort to protect the lives of the crew. Very little is made of the crew’s intimate relationships with the Tahitian women they met on the voyage.

Narratively, this version is the most expansive. After the voyage to Tahiti and the ensuing mutiny, we see Bligh return to Tahiti on the HMS Pandora, narrowly missing Christian and his fellow mutineers. He is greeted by the crew members who did not actively mutiny but could not fit in Bligh’s launch. True to character, he treats them as enemies. The search and recover mission comes to and end when the Pandora sinks. Some of the Bounty crew who were taken prisoner by Bligh are later tried in England, convicted, with some ultimately acquitted as Admiralty reconsiders how superior officers should treat their men. Meanwhile, Christian burns the Bounty at Pitcairn island, choosing exile for him and the other mutineers.

As said above, this version covers the most details of the saga, but is exaggerated and altered in key areas. First, by most accounts, Bligh was harsh by modern standards, but not unusually cruel by 18th century naval norms. One embellished inciting incidents of the mutiny in both the 1935 and 1962 film versions involves Bligh’s keelhauling of a seaman resulting in death. However, this apparently does not appear in the actual Bounty logs.

In relation to that, Laughton’s performance, while iconic, recasts Bligh as a sniveling, potbellied sadist, and this is ultimately where the film falters for me. If Bligh were truly this cartoonishly despotic, he would likely have been thrown overboard long before reaching Tahiti. The portrayal remains entertaining, but a man so utterly devoid of charisma commanding The Bounty feels implausible. This is one of the more striking historical details that all of the films almost never convey, as Bligh is usually portrayed as significantly older and more ossified than he actually was at the time. As far as storytelling goes, Bligh needed to be portrayed this way to justify the mutiny, as the intimate relationships between the mutineers and their Tahitian companions are largely overlooked in this version.

There is also one more small historical liberty taken in this version, and it’s one worth noting. In reality, it was Captain Edwards, not Bligh, who was dispatched aboard Pandora to hunt down the mutineers. That responsibility is reassigned to Bligh in the film, a choice that is less about accuracy than narrative economy. Folding the pursuit back into Bligh’s arc is undeniably more cinematic, sparing the film the awkward necessity of introducing a new authority figure late in the story and keeping the drama anchored to its central antagonist.

The 1935 Mutiny on the Bounty remains a handsome, classically mounted production, buoyed by strong performances. Yet its claims to historical credibility are undermined by an interpretation of Bligh that veers into the grotesque, rendering him a caricature of sadism rather than a rigid, capable naval officer shaped by the norms of his era, whose authority over his crew ultimately unraveled through a convergence of circumstance, temperament, and misjudgment.

Mutiny on the Bounty (1962)

- Release year: 1962

- Director: Lewis Milestone

- Principal cast: Marlon Brando, Trevor Howard, Richard Harris

- Runtime: 185 minutes

- Academy Awards: Nominated for seven Oscars, including Best Picture

This is the definitive version for me in terms of entertainment value. Marlon Brando’s Fletcher Christian is not a heroic archetype like Clark Gable, nor a desperate fool in love like Mel Gibson, but a clearly conflicted man who is uncomfortable with the captain he serves and later unsure whether his rebellion was the right choice. This version has a classic Hollywood feel, but doesn’t feel so outdated that it becomes a chore to watch.

Trevor Howard’s Bligh is also extremely memorable. He is rigid, humorless, and obsessively correct, yet also stoic and charismatic. He is not a monster per se, but a man whose adherence to the “rules of war” and obsession with the success of the mission eclipse any empathy he might possess.

The mutiny in this adaptation, like the 1935 version, is primarily about the command style of Bligh and Fletcher’s moral exhaustion rather than Tahitian temptation. The love affairs exist, but they are not the impetus of the rebellion. Like the 1935 version, Christian mutinies because he can no longer reconcile duty with conscience.

The ending is the most different from both the 1935 and 1984 versions. In this version, after arriving on Pitcairn, Christian appeals to his fellow mutineers to return to England to testify against Captain Bligh. He then dies attempting to save the Bounty after Mills and some of the others set it on fire to ensure there is no way to get back to England. This recasts the character as certain he acted rightly in response to Bligh’s abuses of power, while rejecting a life of isolation on Pitcairn. While the other two versions don’t say what happened on Pitcairn after the end of the movie, this version gets Fletcher’s death right. However, he actually was murdered after life in the bucolic island descended into paranoia and violence.

The most emotionally and cinematically engrossing, even if not the most historically accurate. Brando’s conflicted Christian and Howard’s rigid Bligh feel like real men trapped in incompatible worldviews and are the standout aspect of the movie.

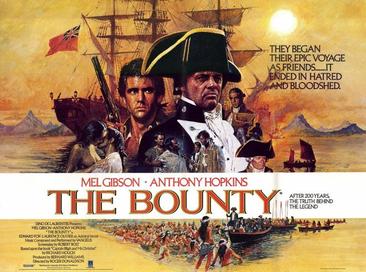

The Bounty (1984)

- Release date: May 4, 1984

- Director: Roger Donaldson

- Main cast: Mel Gibson, Anthony Hopkins, Laurence Olivier, Daniel Day-Lewis, Liam Neeson

- Runtime: 132 minutes

Because you can’t have three films all called Mutiny on the Bounty, the most recent adaptation was shortened to simply The Bounty.

The 1984 version is said to be the most accurate and is also the most modern. Mel Gibson’s Christian is less a man at a moral crossroads, but more a man seduced by freedom and Tahitian women. Anthony Hopkins’s Bligh is more emotionally remote rather than cartoonishly sadistic.

Here, the mutiny is framed heavily around Tahiti. The crew fall in love and experiences a life that makes naval discipline unbearable by comparison. Gibson’s Fletcher Christian adopts traditional Tahitian tattoos and is ultimately forced to leave his pregnant lover behind. Several crew members even attempt to desert before The Bounty departs Tahiti. All of this reinforces the idea that Bligh’s rigidity becomes intolerable precisely because a viable alternative has already been tasted. Bligh’s singling out of Fletcher for punishment on the return voyage to England also deviates from earlier portrayals, which tend to frame Fletcher as leading the mutiny primarily in defense of others subjected to abuse. While it is generally agreed that the mutiny occurred as a result of Bligh’s leadership, this distinction is crucial to balancing the mutineers’ motives and is not fully explored in the earlier film versions of the story.

Christian burning the Bounty at the end is presented less as tragic inevitability and more as romantic severance from the rest of the world. Not much is made of the fact that these men became stateless when they mutinied.

While this version doesn’t go especially deep into the broader details of the story, its emphasis on the mutineers’ attachment to Tahiti and its softening of Bligh make for an interesting attempt at capturing the true emotional underpinnings of the mutiny.

The 1984 film feels the most believable in its on-screen presentation. Less epic in scale. More modern. The performances feel more natural. It lacks the grandiosity of the earlier versions, but gains some intimacy.

What’s True, What’s Not

The Motives for the Mutiny

None of the films fully capture how incremental the mutiny actually was. Framing it as either brutality or romance oversimplifies what was, in reality, a convergence of both.

Captain Bligh’s Charcter

Contrary to all three films, Bligh was not uniquely cruel. He was a strict disciplinarian, but he flogged fewer men than many of his contemporaries. Records suggest only about a dozen total flogging incidents over the entire two year voyage, which was not high by Royal Navy standards. His real failing was arrogance and inflexibility.

Bligh’s Age

William Bligh was born in 1754 and sailed in 1787, which would have made him 33-34 years old during the voyage. The films portray him as an older, entrenched tyrant. In reality, he was young, driven, and still proving himself. While Trevor Howard was 49 at the time of filming the 1962 version, and Anthony Hopkins was 47 during the 1984 production, Charles Laughton was Bligh’s actual age at the time of production.

Fletcher Christian was about 23 to 24 years old.

Fletcher Christian was born in 1764. This makes the mutiny less a clash of equals and more a volatile collision between a rigid young commander and a much younger, emotional subordinate whose relationship began as mentor and protégé.

There was no keelhauling or execution aboard the Bounty.

Despite repeated cinematic depictions, no crewman was killed by Bligh prior to the mutiny. Punishments were harsh but broadly consistent with Royal Navy practice.

The Bounty was not a warship.

It carried no marines and lacked the enforcement hierarchy typical of naval vessels. Bligh’s authority was structurally weaker than the films imply.

Bligh’s navigation after the mutiny was not blind luck.

After being set adrift, Bligh navigated the ship’s launch over 3,600 nautical miles from near Tofua to Timor in 47 days, with no charts and only a sextant and pocket watch. He had previously served as sailing master and navigator on James Cook’s final voyage to the South Pacific, where he was responsible for charting and astronomical observations. The films tend to frame this passage as desperation and endurance, but the success of the voyage rests on demonstrable navigational skill rather than chance.

Only part of the crew supported the mutiny.

Roughly half the men did not join Christian. Several were forced into Bligh’s launch or left behind against their will.

Christian’s end was violent and bleak.

Life on Pitcairn Island rapidly collapsed into violence rather than the exile depicted on screen in two of the three movies. After the mutineers settled there in 1790, tensions between the European sailors and the Tahitian men, fueled by unequal power, disputes over women, and increasing alcoholism, escalated into open conflict. In September 1793, several mutineers, including Fletcher Christian, were killed in a coordinated attack by the Tahitian men. Christian was shot and then hacked to death while working in the fields. What followed was further collapse: retaliatory killings, suicide brought on by alcohol abuse, and additional murders among the survivors. Within a decade, only one mutineer remained alive.

Bligh was formally acquitted and continued his career.

He did not vanish into disgrace. He rose to flag rank and later governed New South Wales, still controversial but hardly ruined.

The Burning of the Bounty

This did happen. Christian ordered the ship destroyed to prevent detection. The act was pragmatic, not symbolic.

The Trials

The 1935 version gets this largely right. Several crew members were captured, tried, and some were executed while others were pardoned.

YPT’s Final Ranking

1. 1962

The most emotionally and thematically balanced from a cinematic point of view. Brando’s conflicted Christian and Howard’s rigid Bligh feel like real men trapped in incompatible worldviews.

2. 1984

Smaller, more intimate, and psychologically modern. Less epic, but more historically accurate.

3. 1935

A landmark production with strong performances, but ultimately undermined by an implausibly grotesque Bligh.

Visit Pitcairn and Relive the Story!

And if you don’t have time to watch any of these adaptations before heading to Pitcairn, don’t worry. We always make time to screen at least two of the three while aboard the Silver Supporter during our Pitcairn Cruise Tour! , both en route to and from the island.