Table of Contents

Part One: A Brief History of North Korean Cinema

“THE GENUINE MISSION OF FILM ART IS TO TEACH THE PEOPLE THE TRUTH OF LIFE AND ILLUMINATE THE ROAD OF STRUGGLE FOR THEM.” – KIM IL SUNG

Most examinations of North Korean cinema tend to rely on condescending or dismissive critiques, often treating the films as curiosities rather than cultural artifacts. Reviewers frequently assess them by the same standards applied to Hollywood or other commercial productions, missing their intended context. To truly understand North Korean films, one must view them within their relationship to the state, where cinema functions as both an artistic medium and a political instrument. North Korea’s founder and president, Kim Il Sung, articulated his government’s use of film himself in a 1960s essay:

Film is the best form of propaganda for the party. It can be shown to multitude of people in

multiple places. Film is capable of projecting a long period of history in just a couple of hours. It is a

better form than novels or newspapers in educating workers. Film is also superior to the theater in a

sense that is not confined by the boundaries of the stage.

One critique of North Korean cinema is that it features repetitive themes. It is true that one would be hard-pressed to find a film where the underlying message is not either the glorification of martyrdom for the state or films in the mold of socialist realism that depict North Korea as a utopia. These themes are oft-repeated, the only major difference being the backdrop. Depending on the production, political messages are delivered through stories set in feudal Korea, during the Japanese occupation, the Korean War, or through a depiction of life in North Korea versus that in the South. To be fair, North Korean produced literature about its film industry admits that the films “[combined] lofty ideological content…with high artistic value.”

Even today, North Korea is not singular in its control of the country’s cinema. Anyone living in China knows that it is very difficult to find an officially released title that is not about China’s civil war, struggle against the Japanese, or an action film imbued with patriotic themes. The 2017 Chinese blockbuster Wolf Warrior 2 is about a Chinese special ops soldier who has to save Chinese nationals when a civil war/plague epidemic breaks out in the country of “Africa.” It is just a North Korean film with a much larger budget. I watched the movie with a Chinese audience and, though the propagandistic elements would appear ridiculous to a foreign audience, people were jumping out of their chairs and cheering, others were crying, and the girl sitting next to me gripped my arm in suspense.

However, governments around the world, including the United States, have long engaged in similar practices. The U.S. Department of Defense, for instance, has collaborated on major productions such as Top Gun (1986 and Top Gun: Maverick in 2022), Black Hawk Down (2001), and American Sniper (2014), shaping narratives that align with national interests and values.

North Korea’s exact cinematic output is difficult to confirm, and even more difficult to research if one does not speak Korean. A 2016 English-language overview of Korea’s cinema, “Korean Film Art,” provides some more detail. The book profiles 177 feature films, 14 TV dramas, 14 documentaries, 11 science films, and 15 animated films. The official number is likely several times high when one considers that some of the TV dramas are long running serials, and that most films feature two-parts, with some having up to 5 installments. Also among the list of feature films is the Nation and Destiny series, arguably the longest-running film series ever with 62 installments produced between 1992 and 2002. Additionally, one must account for the rumors that various films were deleted from the DPRK’s catalog following various purges of actors and directors (see the story of actress Woo In Hee).

North Korea’s film history, and the involvement of the Kim family in its development, dates back to the country’s founding. During the formative years of the DPRK, between 1945 and 1948, when the Soviet Union assisted in establishing the new government, early Korean filmmakers learned valuable production techniques from their Soviet counterparts, with some even sent to Russia for formal training.

The nation’s first feature film, My Home Village (1949), directed by Kang Hong Sik, marked the beginning of North Korean cinema. The film reflected the themes of liberation and national pride that would become central to the country’s cinematic identity, portraying Kim Il Sung’s leadership in the struggle against Japanese occupation as a symbol of unity and independence for the newly founded state.

According to her official biography, Kim Jong Suk, the first wife of Kim Il Sung and mother of Kim Jong Il, contributed to the production of My Home Village. The film not only established the foundational narrative of national liberation under Kim Il Sung’s leadership but also became a lasting cultural reference point within North Korean cinema. When Kim Jong Il later assumed a key role in the country’s film industry, state media often evoked My Home Village as an early milestone in the nation’s cinematic tradition, linking it to his own vision of film as both an artistic and ideological medium.

From Great Man and Cinema:

One spring day in 1949 when he was 7 years old he…joined in previewing the working film My Home Village, the first of its kind in Korea.

The film showed the winter scenes with falling snow. At this sight Comrade Kim Jong Il shook his head dubiously and told an official of the film studio that he wondered why no snow was found on the heads and shoulders of the characters while it came down copiously.

The official blushed with shame in spite of himself because because Comrade Kim Jong Il was right. He noticed that a bad job was made of trick shots.

Comrade Kim Jong Il again remarked that the snow was not lifelike, and asked the official if it was bits of cotton wool.

Again. Bits of white cotton wool were sprinkled to make them look like snowflakes, but they were too crude to produce the intended effect. Afterwards, the scenes were re-photographed.

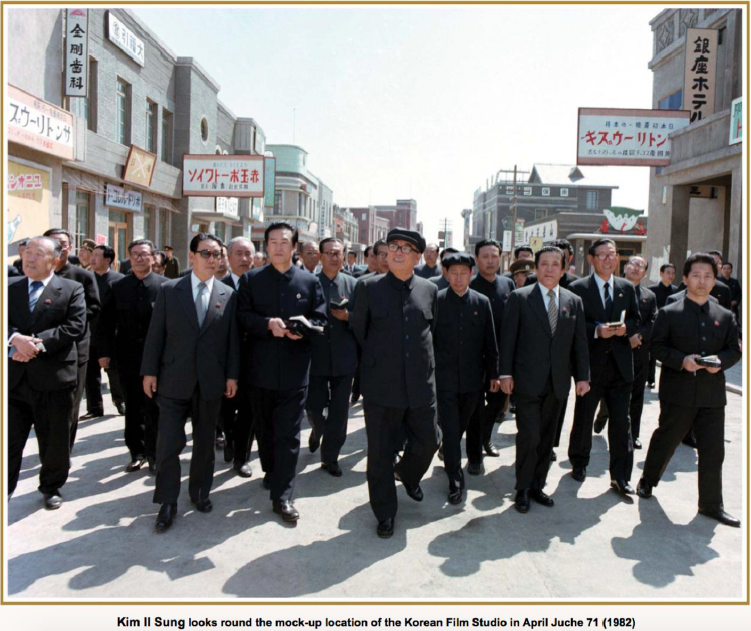

One might be surprised to learn that the North Korean film industry grew to include multiple studios, organizations and institutions. The Korean Film Studio was founded in 1946 by Kim Il Sung and later renovated and expanded under Kim Jong Il. The studio is famous for having produced some of the DPRK’s seminal films like The Flower Girl and the aforementioned The Nation and Destiny series. The sprawling, one-million square meter complex features backlots depicting feudal Korean villages, Korea under Japanese rule, Western-style streets and houses, a working railway line and a South Korean street replete with the prerequisite details of decadence like Cocoa-Cola ads, brothels and a movie poster for The Seven Year Itch. At one time, the studio employed up to 1,200 personnel. Today backlots and facilities are open to tourists and the studio, its crew, personnel and practices were featured in the 2012 Singaporean documentary The Great North Korean Picture Show as well the 2013 Australian documentary Aim High In Creation.

Other facilities located in Pyongyang include: the TV Drama Studio (Est. July 22, 1973), the Korean Documentary and Science Film Studio (Est. July 1, 1946), the Korean April 26 Children’s Film Studio (Est. 1957), the Korean Cinema and Radio Musical Company (Est. May 7, 1958), the Pyongyang University for Dramatic and Cinematic Art (Est. November 1, 1953), the Pyongyang Film Processing Laboratory (Est. July 27, 1973), the Cinematic Scientific Research Institute (Est. April 28, 1961), the Korean Scriptwriting Company (Est. June 14, 1948), the Korea April 25 Scriptwriting Company (Est. September 13, 1980). The Korean Film Export & Import Corporation is responsible for worldwide and home video distribution of Korean titles as well as the acquisition of foreign titles for Korean audiences.

The Pyongyang International Film Festival was founded in 1987, originally as the Film Festival of Non-Aligned and Other Developing Countries, and has been held bi-annually since 1990. The event has grown to include a wide selection of international films from British comedies, U.S. coproductions, and even featured the first horror film to be shown in North Korea. PIFF was held originally at the brutalist, concrete International Cinema House on Yanggak Island near the Yanngakdo Hotel. Since 2014, it has been held at a variety of cinemas and theaters around the city.

Part Two: With the Century

“THEMES SHOULD BE TREATED IN SUCH A WAY AS TO ENHANCE THEIR POLITICAL IMPORTANCE.” – KIM JONG IL, ON THE ART OF CINEMA, 1973

While the themes found in Western cinema often change with the tastes of audiences to enhance marketability and, thus, profitability, North Korea’s cinematic themes – not unlike other communist and socialist states – have changed based on the policies being championed by the state.

Contrary to popular belief, Korean filmmakers are encouraged to watch foreign films, albeit from a carefully curated list. They are not, however, supposed to be influenced by themes considered ideologically unfit. “Any feature film that contributes to people’s lives is good, but those that do not represent the ideals of the people, such as those that talk about robbery or despair, are not accepted,” Korean Film Studio administrator Ri Jong Duk once told a reporter. Some foreign titles that I have heard referenced by North Koreans are Gone With The Wind, Titanic (the film’s theme is a popular karaoke number for Koreans who refer to it simply as “Titanic” rather than “My Heart Will Go On”), Braveheart, Rocky, Goldeneye, The Mask starring Jim Carrey, The Sound of Music and – strangely – Big Daddy starring Adam Sandler.

According to journalist James Bell, Jang In Hok, director of 2006’s A Schoolgirl’s Diary, told him in an interview that in 2007 Kim Jong Il put all of the North Korea’s film directors on an eight month hiatus and sequestered them in a hotel. Their assignment was to watch 250 films selected by Kim Jong Il, who is said to have had a collection of 20,000 foreign films. According to director Shin Sang Ok, Kim Jong Il’s favorite films included Rambo, Friday the 13th and the James Bond series.

Declassified documents from the Clinton administration negotiations with North Korea devote notable attention to Kim Jong Il as an avid cinephile. Reports sent back to Washington by the delegation of Madeleine Albright following her 2000 visit to Pyongyang note that Kim Jong Il often used discussions about movies as an icebreaker, remarking that he kept up with new releases “every ten days or so.” He reportedly first asked Albright which recent movie she had last seen. She replied that she had watched Gladiator, to which Kim responded that he had recently viewed Amistad by Steven Spielberg, describing it as “very sad.” He later told Wendy Sherman, who was in Pyongyang as a special advisor, “I own all the Academy Award movies. I’ve watched them all.” Other accounts note that he claimed to “usually agree” with Oscar nominations and even suggested that the life of Kim Dae Jung, the architect of the Sunshine Policy and the first South Korean president to visit Pyongyang, whose journey spanned dissidence, exile, and ultimately the presidency, would make for a compelling film.

Things have changed many times in the 75 years since the first North Korean production. Naturally, the films produced during the Korean war were intended to boost the morale of both the beleaguered troops and civilians. After the war, with the exception of some forays into the fantasy genre, the films championed themes of the Chollima movement, a campaign to mobilize the masses to work harder to develop the nation’s fledgling economy.

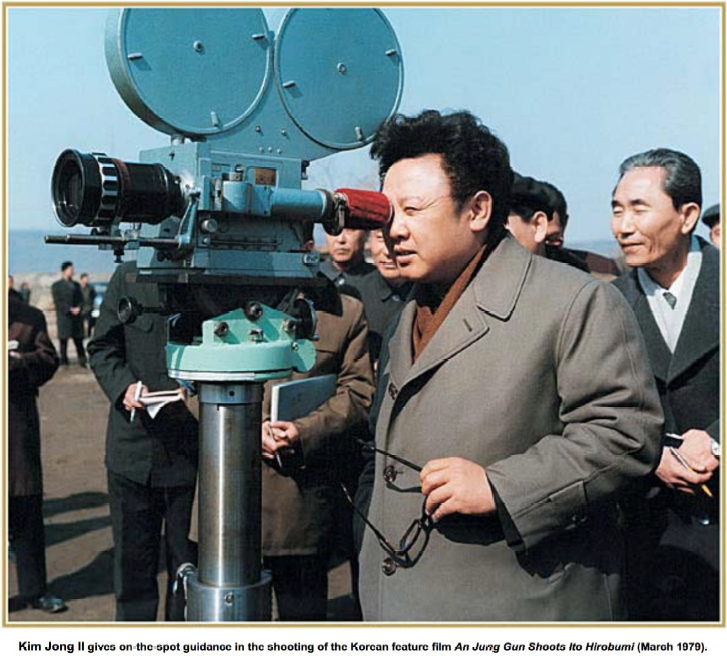

The most notable North Korean films were made from the 1960s to the 1980s, when Kim Jong Il supervised the production of a slate of films to embody North Korea’s Juche (“self-reliance”) philosophy, heeding Kim Il Sung’s 1966 call to “develop [art] in a revolutionary way, reflecting the Socialist content with the national form”. In 1973, the state published Kim Jong Il’s guide to filmmaking, On the Art of Cinema. The book covered Kim Jong Il’s instructions on screenwriting, directing, acting and editing as seen through the prism of North Korea’s unique confluence of socialist realism and the Juche philosophy.

“No production of high ideological and artistic value can evolve out of a creative group whose members are not united ideologically and in which discipline and order have not been established,” the Dear Leader told his subjects.

During the 1980s, North Korean cinema began to explore new directions as Kim Jong Il collaborated with Shin Sang Ok, a renowned South Korean filmmaker, to create works aimed at both domestic and international audiences. These productions reflected a heightened focus on artistic quality and cinematic innovation, marking a distinct period in the country’s film history.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the resulting economic difficulties of the 1990s, North Korean cinema shifted once more toward more traditional and didactic storytelling. As the country faced serious challenges in production and distribution, films increasingly focused on themes of self-reliance, perseverance, and national unity. During this time, cinema served as an instrument of encouragement, emphasizing the need to endure hardship and maintain faith in the nation’s strength throughout the period known as the “Arduous March.”

Today, North Korea’s film production volume is lower than in previous decades. This shift may reflect the government’s decision to allocate resources to other cultural and technological priorities, as well as the broader availability of approved foreign films, particularly from China and Russia, which now supplement the country’s domestic cinematic offerings.“Our films are not so good as past days,” one guide told me. “The number of new films is not so much. They can produce better films when our country is rich and prosperous. Money, culture and politics is connected closely, I think. Economy increases and culture can rise up.”

Part Three: Like Humans Do

“CINEMA IS THE ART OF ACTION AND THE ART OF LIFE.” – KIM JONG IL

It is easy for outside observers to dismiss North Korean films as peculiar or exaggerated, but they hold a meaningful place within the country’s cultural life. For many viewers, these works are more than state productions – they are familiar stories that evoke nostalgia and shared experience. While it can be difficult for outsiders to imagine the everyday rhythms of life in the DPRK, it is worth noting that Koreans watch, discuss, and even joke about these films much as audiences elsewhere do with their favorite Hollywood releases.

I once brought up Order No. 27 to my guides and after a few drinks we were acting out the famous scene where a North Korean commando drives a jeep with his foot while simultaneously machine-gunning South Korean and American troops. With another guide, we got a big kick out of planning an aptly title sequel, Order No. 28.

Another time, while looking at DVD’s, I stumbled across a later film by actress Yun Su Gyong who played the beautiful female lead 1982’s Wolmi Island. The two female guides accompanying me giggled about how the actress had become “soooo old!” Another guide got misty-eyed when a waitress treated us to a rendition of the haunting theme from Wolmi Island. And a scene where Wolmi Island‘s lead character rests his hand on a just-fired cannon without burning himself is a famous blooper. “This is very funny for Koreans because after a battle a cannon is hot!” my guide exclaimed.

Last, Korean girls will giggle and tell you they like Hong Kil Dong because the lead “is so handsome!”

Part Four: Five Films You Must-See

“THE DIRECTOR IS THE COMMANDER OF THE CREATIVE GROUP.” – KIM JONG IL, ON THE ART OF CINEMA, 1973

Where to start? Around 100 North Korean titles have been made available with English subtitles. These include obvious choices such as The Flower Girl and Hong Kil Dong, while other famous and seminal titles remain unavailable, such as Sea of Blood and Star of Korea. Pulgasari and other films by Shin Sang Ok were removed from the DPRK’s film library following his 1986 defection; a travesty considering his films feature some of North Korea’s most ambitious filmmaking.

Below are five titles which are both entertaining in a Western sense, but also provide an overview of North Korean cinema’s favorite idealogical themes. These titles are mostly available on YouTube with English Subtitles and also frequently found on DVD (usually for about 5 Euro each) in souvenir shops frequented on any of YPT’s North Korea tours.

The Flower Girl, Dirs. Choe Ik Gyu and Pak Hak, 1972

Synopsis from Korean Film Art:

With little sister, Sun Hui, who got blind by the cruelty of the landlady, Kkotpun sells flowers to pay for the medicine of her mother who has fallen sick from slavery as landlord Pae’s servant. In spite of her devotion, her mother dies and Kkotpun sets out on a long journey to see her brother, who was unjustly thrown into prison years before. When she hears of her brothers death from a jailor, she attempts her own life, but thinking of her blind sister, she comes back home. Hearing her sister was lured away by the landlord, she protests against the landlord. But she is severely beaten and locked in a store. On the other hand, her brother Chol Ryong who joined the Korean Revolutionary Army after his escape from the prison, stops over at a mountain hut near the village. There he finds Sun Hui who was rescued from death by the owner of the hut. He encourages the villagers to finish off the landlord and his minions and saves his sister Kkotpun. Kkotpun follows her brother to join the anti- Japanese revolutionary struggle led by Kim Il Sung.

The Flower Girl is by far the most famous North Korean Film and regarded by the state as an Immortal Classic. The film is based on the “revolutionary opera,” which is said to have been written by Kim Il Sung when he was imprisoned by the Japanese for his revolutionary activities. In Kim Il Sung’s memoirs, With the Century, he noted that the play was first performed by Koreans in Jilin province on the 13th anniversary of the October Revolution. And, according to official publications, the play was not performed until it was “improved and adapted for film, and re-written as a novel under the guidance of” Kim Jong Il.

The film is the quintessential example, as pure a propaganda film as one could hope to see. Production began in April, 1972, and the film was co-directed by Choe Ik Gyu and Pak Hak. Choe had been entrusted by Kim Jong Il with the 1968 film adaptation of another Immortal Classic and revolutionary opera, Sea of Blood. Pak Hak, had starred in 1953’s Scouts, a war film shot during the Korean War, and would go on to direct 1974’s The Fate of Kum Hui and Un Hui.

The film was shot almost entirely on studio sets and a impressively convincing backlot dressed as Korea under Japanese occupation. The film follows a penniless flower girl who has her spirit stomped time and again by the cartoonishly malevolent Japanese, who let her family rot to death under the weight of extreme poverty. The film is a steady descent into unending pity, until her brother (representing Kim Il Sung’s invincible and noble Korean People’s Revolutionary Army) appears on the scene to overthrow the landlord at the center of her misery.

What’s interesting about The Flower Girl, and the many North Korean films produced in this style, is the almost total absence of the formal flourishes that the European and American films had introduced to the medium by the 1970s following the French New Wave. There is little in the way of style or embellishment to underscore dramatic beats, giving the film a straightforward, workmanship quality. The blocking of actors is staged with an artificial rigidity, often leaving key faces out of view at moments where Western audiences are accustomed to expect a reverse shot or close up. Many scenes are shot in an artlessly framed wide and stay there, regardless of the dramatic value of what is being said.

Nevertheless, the film has several worthwhile images with an undeniable gauzy and ethereal quality, used to especially flattering effect in the opening as our protagonist gathers flowers to sell on the streets once the market opens. At its most attractive moments, the film feels as if it were released closer to the period it portrays, looking more like a product of the early technicolor days of Hollywood instead of the 1970s. Artistic direction aside, this is likely the product of older, outmoded lenses and equipment used, as well as the filmmakers holding tightly to a rudimentary emulation of Western and Soviet films they admired without understanding the visual logic underpinning them.

One could watch The Flower Girl and wonder if the filmmakers know the power of a close up, or what, if anything, a creeping camera move communicates to the subconscious of the audience – or if they just see these choices as interchangeable units of communication, each as effective as any other. Unlike Western cinema which had been sharpened for decades under a traditional studio system and had begun to break free of those traditions into experimental pop territory by the 1960s, The Flower Girl represents a much earlier step in a nation’s love affair with the movie camera.

The Flower Girl played at a number of Eastern Bloc festivals and became the first international award-winning North Korean film when it won a Jury Prize at the 1972 Karlovy International Film Festival in Czechoslovakia. The film’s international recognition must have lead to a boastful article in a 1974 Korean Review which claimed: “In recent years our film art has created an unprecedented sensation in the world’s filmdom… The revolutionary people of the world are unstinting in their praise of this feature film and other monumental works, calling them ‘the first-class films by international standards’, ‘the most wonderful movies ever produced’ and ‘immortal revolutionary and popular films’.”

The movie was also released in China at the outset of the Cultural Revolution. It was apparently so popular that some Chinese cinemas introduced 24 hour programming for the movie. One North Korean guide told me that Chinese tourists still ask about the film. In 2009, actress Hong Yong Hee, who portrayed Kkotpun, received Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao when he arrived on a state visit to the DPRK.

Images of Kkot Bun can be found sprinkled throughout North Korean culture, most notably on the one Won note (no longer in circulation following several rounds of currency reforms) as well as on a huge mural at the entrance of the Pyongyang Grand Theatre. According to North Korea state media, the play has been performed over 1,400 times in 40 countries. In South Korea, the film was banned as communist propaganda until 1998.

Watch The Flower Girl online for free with English subtitles HERE.

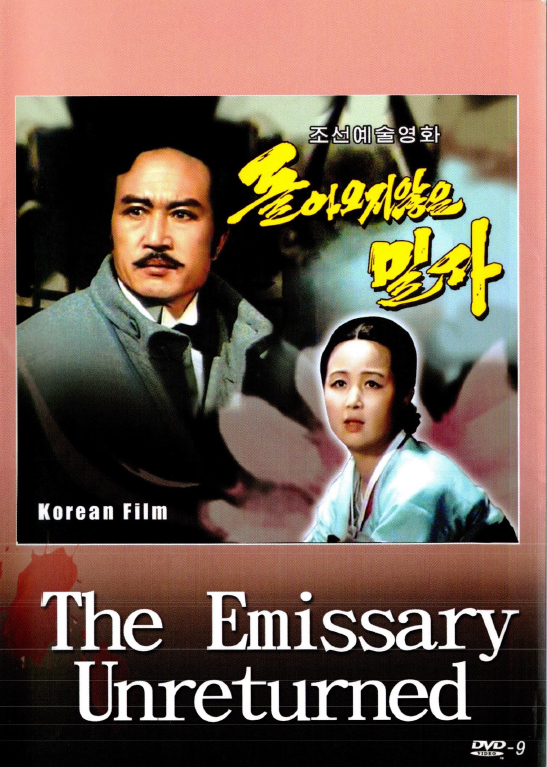

The Emissary Unreturned, Dir. Choi Eun Hee and Shin Sang Ok, 1984

No Korean synopsis available.

According to several Western accounts, in the late 1970s Kim Jong Il, seeking to revitalize North Korea’s film industry, kidnapped Shin Sang Ok, one of South Korea’s most prominent directors, and his former wife Choi Eun Hee, a celebrated actress, to the DPRK to help strengthen its cinematic output. After a period of cultural and ideological adjustment, the couple was given significant creative freedom and resources to produce films aimed at enhancing the prestige and international recognition of North Korean cinema.

Under Kim Jong Il’s supervision, Shin directed several ambitious projects that demonstrated both technical innovation and artistic vision. His work reportedly received strong support and substantial production budgets, allowing for large-scale set pieces and practical effects that were rare for the time. Later, in 1986, while traveling abroad for film-related work in Vienna, Shin and Choi defected back West, bringing an end to one of the most unusual and discussed collaborations in film history.

Shin and Choi detailed the alleged kidnapping in their own lengthy Korean-language autobiography Our Escape Has Not Yet Ended. The story has been covered in Paul Fischer’s English-language book A Kim Jong Il Production and in the recent documentary The Lovers and the Despot. However, critics of their story have pointed out that though Shin was once one of South Korea’s most heralded filmmakers in South Korea, the ROK government had revoked his filmmaking license in 1975, three years prior to his 1978 arrival north of the DMZ. Additionally, Shin’s close friend, Japanese journalist Tetsuo Nishida, claimed in his book Fictional Image that prior to his disappearance, Shin had told Nishida that he had received an offer to make films for the North. Whatever you think of how Shin got to North Korea, his impact of the country’s cinema is undeniable.

Though Shin and Choi’s names have been removed, the Emissary Unreturned is the only film by Shin Sang Ok found easily in the DPRK on DVD (though strangely absent in the DPRK 2016 film catalog, Korean Film Art). This historical drama, based on the play Hyolbun Mangukhoe (Resentment at the World Conference), is also credited – according to official accounts – to Kim Il Sung himself. It was later elevated to the status of one of the country’s five great revolutionary plays. Shin elected to give Choi directing credit, and she won the Special Jury Prize for Best Director at the 1984 Karlovy International Film Festival. At the same festival, Shin and Choi held a press conference in which they announced that they had willingly defected to the North. The film also played on London. Though the screening was picketed by South Koreans, it was reviewed positively as “a broad, oriental-flavoured theme in guises ranging from the march-like to patriotic and romantic for its story of Korean heroism at the turn of the century – a major surprise.”

The story details the efforts of three Korean emissaries at the 1907 Second Hague Peace Convention, dispatched in secret by the Choson Dynasty’s King Gojong in a last ditch attempt to thwart the annexation of Korea to Japan. The film hits all the classic North Korean cues as the patriotic but naive Koreans attempt to buy political influence by delivering lavish gifts to representatives from other nations. They are ultimately out-influenced by the Japanese and betrayed by the American delegation. Eventually, lead emissary, Li Jun, delivers an impassioned speech in front of the entire conference before shocking the other delegations by plunging a dagger into his stomach, committing seppuku on the convention floor.

Though the seppuku sequence is a complete fabrication and many of the events as depicted in the film are hyperbolic, it is true that Gojong sent Li Jun, Yi Sang Seol and Yi Wi Jong to the Second Hague Peace Convention. However, the secret emissaries were not even allowed access to the convention hall and, instead, delivered their message through a press conference. The film’s title is also accurate as Li Jun was not to return; he was found dead in his hotel room a few days after the failure of his mission.

The Emissary Unreturned was the first North Korean film shot abroad, though safely behind the iron curtain in Prague, Czech Republic, which doubled as the Netherlands (with the help of stock footage of The Hague). While Western characters were portrayed previously either by Koreans donning comical make-up, visitors from the Eastern Bloc, or the four U.S. Army soldiers who defected North, this film also featured North Korea’s first European ensemble cast. The film was shot at Barrandov Studios in Prague, where, the following year, the same studios were used for Milos Forman’s Amadeus.

The Emissary Unreturned is the only film on the list not available online with English subtitles. Korean speakers can view it without subtitles HERE, or you can track down a copy during one of YPT’s North Korea tours.

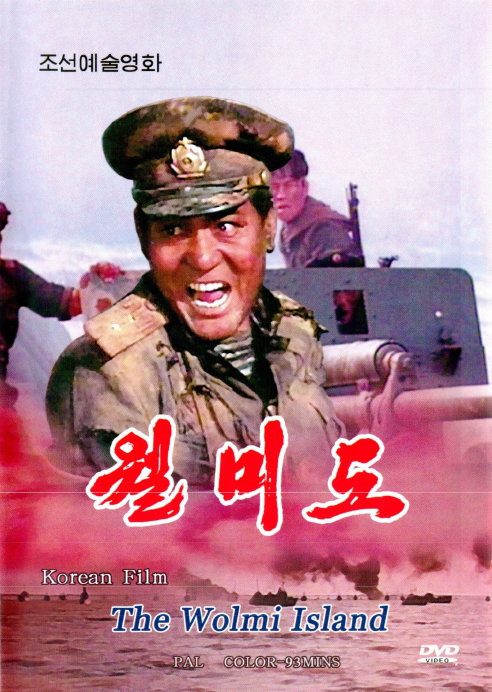

Wolmi Island, Dir. Jo Kyong-sun, 1982

Synopsis from Korean Film Art:

When the fatherland is faced with a grim trial, Company Commander Li Tae-Un and his coast artillerymen go into battle with a heroic resolve.

On the first day of the battle, they frustrate the enemies’ attempt to land, but with heavy casualties. With death-defying determination not to waste the blood of the fallen comrades they deal an annihilating blow to the enemy once more on the second day. What left are a few gunmen, one gun, and half a dozen rounds of shells. They become human shells and fight like phoenix to defend Wolmi Island from the enemy’s landing for three days.

Produced by the February 8th Film Studio (later, the April 25 Film Studio) with the cooperation of the Korean People’s Army, this is North Korea’s answer to classic war epics like The Battle of Britain and A Bridge Too Far. As we know, at the outset of the Korean War, North Korean troopsquickly overran the majority of South Korea. The tide of the war changed in September, 1950 when MacArthur’s troops captured Incheon through a series of landings. One of these landings was on the small island of Wolmi, one-kilometer off the coast of Incheon. At 6:30am on September 15, U.S. troops stormed the beach at Wolmi Island. By noon, they had captured the island with only 14 casualties. Wolmi Island, the film, spins this defeat into a spiritual victory.

History aside, the film is emotionally effective. Penned by screenwriter Li Jin U, writer of the multi-part spy series Nameless Heroes (now-famous for featuring major roles played by the four American GI’s that defected to North Korea),Wolmi Island tells the epic tale of Commander Li Tae-Un as he and his small company heroically defend the island for three days with only four large guns. According to the film, this small group of soldiers, with iron-willed resolve to “never yield the road to Pyongyang,” destroyed dozens of enemy ships and aircraft and held off MacArthur’s siege for three full days before finally succumbing to tremendous enemy superiority.

The film also features a mesmerizing theme, introduced on-screen by actress Yu Su Gyong as the endearing 17 year-old KPA radio operator, Yong Ok:

Dead or alive, we’re in your embrace,

I call you with boundless emotion,

O, my country that is called mother,

I know it’s the embrace of the general.

The film features plenty of action, with shoot-outs and exploding boats and aircraft. In one sequence, a soldier swims out amongst the enemy warships and destroys one when he manually thrusts a mine into its hull. Upon observing this, a captured American soldier held prisoner in the North Korean trenches laments: “We can’t beat them. America may win a battle but not war. MacArthur’ll suffer the shame of defeat all his life. Curse to MacArthur!”

To erase any doubt as to the veracity of the story, the film ends with the binding words of Kim Il Sung:

The shore battery men of Wolmi Island fought well. They fought bravely to the last man to ensure the strategic retreat of the People’s army as ordered by supreme HQ’s and checked the enemy’s landing for 3 days. We cannot forget their heroic services.

It is worth noting that this film was made in 1982 when Kim Jong Il was revamping the Korean film industry to make films for commercial export. With that in mind, Screenwriter Li Jin U may have been able to write a more impactful film had he focused on the real fact that prior to the landing at Wolmi Island, U.S. warplanes dropped a total of 93 canisters of napalm on the island and killed scores of civilians. So thorough was the bombing that one U.S. Marine pilot wrote in his report: “The mission was to saturate the area so thoroughly with napalm that all installations on that area would be burned…the flashes observed on the ground indicated the intensity of the fire to be accurate enough to destroy any about.”

Watch Wolmi Island on YouTube with English Subtitles HERE.

Pulgasari, Dir. Shin Sang Ok, 1985

Pulgasari, certainly among the most infamous cultural exports of North Korea, is an altogether different beast. While Godzilla was born of the Japanese’ commentary on nuclear energy, Pulgasari was born of the class struggle. The film is unusual in the North Korean cinematic canon for both its fantasy subject matter and visual dynamism. Owing to director’s Shin Sang-Ok’s long career as a revered South Korean director, the film calls upon a wealth of flashy camera techniques and more appealing art direction than most previously produced North Korean films. The soundscape, too, is more complex. The synthesized score is at once a product of its time and evocative of traditional Korean melodies.

The film is set in feudal Songdo (today, Kaesong) Korea, where the virtuous peasants are terrorized by a tyrannical governor who seizes all of their iron tools and utensils. A blacksmith is jailed when he refuses to turn the tools into swords for the governor’s army. In jail, he sculpts a glob of rice into a small figure of a horned creature. “Because I made you with the last of my true heart,” he tells the sculpture during an emotional monologue, “please save humanity in my place.” The blacksmith dies and his daughter Ami finds the sculpture in his hand.

Later, Ami pricks her finger while sewing and a drop of blood lands on the sculpture, which comes to life and eats Ami’s sewing needle. From there, it consumes all of the iron in sight and grows into a giant monster, Pulgasari. Pulgasari fights alongside the farmers to take down the wicked governor. However, Pulgasari outlasts its usefulness, and, after devouring the enemy’s weapons, he begins to scarf down the farmers’ tools. Ami hides in a large bell and is consumed by the monster which causes Pulgasari to explode. Critics of the DPRK have suggested that Shin hid within Pulgasari a criticism of Kim Il Sung; the once champion and liberator of the people was now depriving his people to enrich itself.

While the film is often mocked as a so-bad-it’s-good Godzilla rip-off, it actually has more legitimate ties to Gozilla than many knock-offs. Shin hired Toho Studios hot off the heels of Godzilla 1985 to design Pulgasari. Kenpachiro Satsuma, who donned the monster suit in Godzilla 1985 was also hired to portray Pulgasari on screen. Satsuma and 15 Toho technicians first worked on the film at Beijing Dian Ying Studios and then in North Korea where they were housed in a mansion that purportedly belonged to Kim Jong Il.

Not only did Satuma later say that he preferred the Pulgasari suit to the one used in Godzilla 1985, he later told an audience at the 2014 Bib Wow Comicfest: “When people saw Pulgasari, people from Toho were actually saying it was more entertaining than Godzilla, 1985…” Satsuma later wrote abook about the experience called North Korea Seen Through The Eyes of Godzilla. Unfortunately, ithas yet to receive an English translation.

For Pulgasari, the Toho technicians employed the same photographic tricks of scale used in Godzilla 1985, though to lesser effect. The titular monster, Pulgasari, is the only skyscraper-scale beast in the film, so we have little reference for a true sense of his size. More problematic yet, being a period piece, there is no towering skyline for us to compare him to. He is typically seen lumbering among plastic treetops or against a bright blue sky, which fails to capture his intended size in the same way as a lizard ravaging a cardboard Tokyo.

However, the inverse is pulled off beautifully. Pulgasari begins his life small enough to fit inside the palm of our protagonist’s hands, and a scene early on where he sparks to life in her sewing box works rather convincingly. The scene is achieved using an oversized set of the box for the monster to interact with while Ami looks on in disbelief, complete with enormous scissors and needles for scale.

Pulgasari makes generous use of long zoom lenses, the camera always lurching into characters as they deliver dialog or trade blows. It taps into some of the raw kineticism of a Shaw Brothers production, with shaky handheld camerawork and brisk edits punctuating the action, capitalizing on the chaos between cuts to energize the battle scenes. This does lead to some confusing, nonexistent geography in the large-scale battle sequences pitting Pulgasari and the peasant army against the governor’s minions, though this isn’t an uncommon gripe in monster movies originating from any country.

The film was a huge hit in North Korea. One of my guides in North Korea’s rural North Hamgyong province told me that when the film was released, he had to stand in the back of the theater in order to see it. Though Shin Sang-Ok’s name was subsequently scrubbed from its credits, with credit going to his assistant director Chong Gon Jo, the film is unavailable today inside the DPRK. We owe the fact that copies still circulate to Japanese distributor Raging Thunder which released the film on VHS and in select theaters in Japan in 1998.

When I contacted the man behind Raging Thunder’s release, the eccentric Fumio Furuya, he was hesitant to discuss his involvement. “Yeah, I did distribute that movie,” he said. “But the movie had already been…subtitled by someone else and I was just asked to distribute it. So, I wasn’t actually digging North Korean stuff…I mean, I’m not saying I don’t wanna do it. But it’s just that I don’t know enough to be interviewed and Japanese media might go against me if I do that.”

Watch Pulgasari for free online with English subtitles HERE.

Order No. 27, Dir. Jung Ki Mo and Kim Un Suk, 1986

Synopsis from Korean Film Art:

Failing to make contact at Yongchon Station due to an unpredicted incident in the train, the special task team makes a forced march to the next rendezvous. They brave through all dangers of the enemy’s frequent search, persistent chase and ever-changing situations. Although they experience heart-rending pain and agony of losing some squad members on the way, they fulfill the mission with credit, cherishing the order given by the fatherland as trust in them.

If Wolmi Island is North Korea’s answer to war classics, Order No. 27 is its answer to The Inglorious Bastards. According to Johannes Schonherr, author of North Korean Cinema: A History, thefilm is a clear indication of Shin’s impact on North Korean filmmaking and the filmmakers were sointent on delivering a quality action film that several actors were inured during filming.

Also produced by the February 8 Film Studio (later, April 25 Film Studio), Order No. 27 is set during the Korean war and centers around a group of commandos stuck behind enemy lines. While attempting to fulfill their mission, the commandos find themselves in a variety of precarious situations which deliver some well executed shoot-outs, a taekwando fight sequence filmed on top of a moving train, and a nod to the 1976 ax murder incident when a North Korean uses an ax to murder a South Korean soldier.

Finally, the film climaxes gloriously when the captain grabs onto an enemy helicopter at takeoff and blows it up with grenades up in the air. Just before the chopper explodes, we hear his inner monologue: “Comrades, I entrust the mission to you. Now I am proud because I can fulfill the mission. The happiness of our Party’s soldiers is the devotion to our great leader and party.”

Order No. 27 is pure camp, great entertainment, and could have been made only in North Korea.

Watch Order No. 27 for free online with English subtitles HERE.

Part Five: Footsteps

“SOCIALIST ART AND LITERATURE HELP PEOPLE TO DEVELOP A PROPER OUTLOOK ON THE REVOLUTION AND LIFE, TO NURTURE ENNOBLING AND FINE MENTAL AND MORAL TRAITS, AND TO TAKE AN ACTIVE PART IN THE REVOLUTION AND CONSTRUCTION. THEY ALSO PLAY AN IMPORTANT LEADING ROLE IN SOCIAL CIVILIZATION.” – KIM JONG UN

During my visit to North Korea in August 2017, I was told that Kim Jong Un, like his father Kim Jong Il before him, had taken a personal interest in the country’s domestic film production and had issued directives for the North Korean film industry to be modernized in a “Hollywood style” model. If that is true, let’s hope the Great Successor can fulfill his late-father’s wish to bring international recognition to North Korean cinema. That will not be easy, and, whatever happens, I’ll happily settle for Order No. 28.