Before there was SpaceX or Blue Origin, before the first manned Shenzhou flight or China’s lunar rover rolled across the Moon, there was only sand, steel, and ideology. Tucked deep inside the deserts of western China, entire towns were constructed for one purpose only—to send a new communist superpower hurtling into the cosmos. These were the Space Cities. Some are still active, others are half-forgotten relics of a dream that once rivaled the ambitions of NASA and the Soviet Union. Visiting them today is like time-traveling into the hardware of a vanished future.

China’s space race did not begin in glossy tech campuses or cosmopolitan metropolises. It began with a deported scientist, Cold War paranoia, and a country rebuilding itself from the rubble of civil war. Qian Xuesen, the father of China’s space program, was a brilliant rocket engineer expelled from the United States during the McCarthy era. His return to China in 1955 marked the beginning of an industrial and scientific campaign that would eventually produce nuclear weapons, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and manned spaceflight.

But these achievements did not come from Beijing or Shanghai. They emerged from purpose-built towns in the deserts of Gansu, Qinghai, and Xinjiang—towns that today remain haunted by their spacefaring past.

Table of Contents

Xining: The Forgotten Origin

The journey into China’s Cold War space program begins in Xining, a high-altitude city in Qinghai province. In the 1960s and 70s, this frontier city was a logistical hub for scientists, engineers, and military planners heading west into classified territory. While most tourists pass through on their way to Tibet, those with a keen eye for space history will find remnants of its aerospace legacy scattered in obscure museums and university campuses.

Some PLA-affiliated institutions still quietly teach aerospace engineering, and there are whispers of old bunkers and test labs hidden in the surrounding hills.

Jiuquan: China’s Baikonur

From Xining, high-speed trains cut across the Qilian Mountains into Gansu province and arrive at Jiuquan, the oldest and most iconic of China’s Space Cities. Just outside this dusty frontier town lies the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center, or JSLC, the beating heart of Chinese rocketry. While foreigners are not permitted inside the facility, its presence dominates the landscape and local psyche.

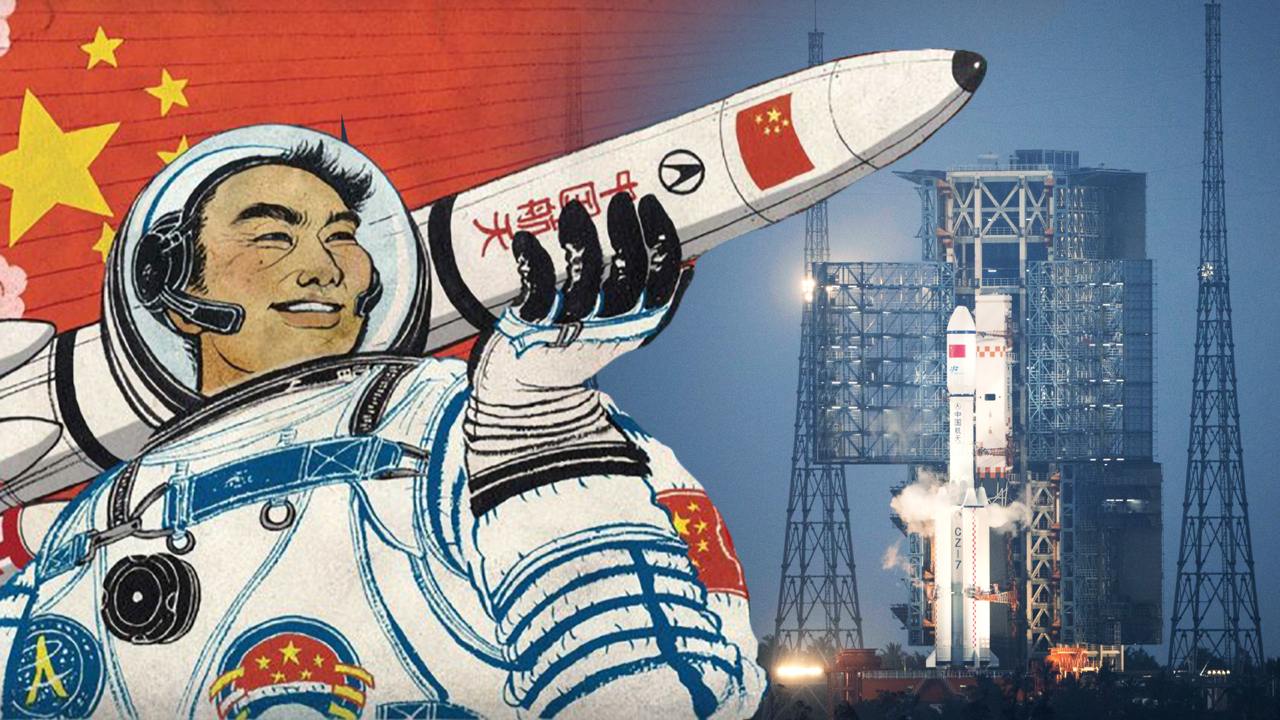

Dongfeng Aerospace City, a partially inhabited workers’ town built to support the launch site, stands as a surreal blend of living infrastructure and crumbling nostalgia. Taikonaut statues stare blankly from plinths, mosaic murals celebrate Maoist triumphs over gravity, and a defunct “space theme park” lies rusting at the edge of the city.

There are also small public museums, often erratically opened, where faded Shenzhou mockups and old reentry suits sit beside dusty dioramas and missile schematics. Propaganda posters from the 1980s still adorn the walls of schools that once trained aerospace engineers.

Outer JSLC: The Legal Limit

Although the core of JSLC is strictly off-limits, travelers with curiosity and a long lens can skirt the boundaries of the launch complex. Decommissioned checkpoints, observation hills, and radar domes are visible from afar. Local markets even sell unauthorized Taikonaut memorabilia, ranging from commemorative lighters to off-brand mission patches. The military presence is discreet but constant. This is still an active site for satellite launches and defense-related space activities.

What sets Jiuquan apart from glossy spaceports like Kennedy or Baikonur is its hybrid status. It is both relic and reality, monument and mechanism. China’s first man in space, Yang Liwei, launched from here in 2003, yet the roads leading to the site are cracked, lined with half-empty housing blocks and fading billboards of space conquest. It is a working fossil.

Yumen: Ruins in the Rocket Belt

A few hours’ drive from Jiuquan lies Yumen, one of China’s most atmospheric space ghost towns. Once a booming oil city and a hub for aerospace metallurgy, Yumen today is marked by decay. Residential blocks built for engineers and rocket specialists stand empty. Schools and sports grounds are slowly collapsing into the sand. Yet among the ruins, space still lingers.

The town features a peculiar Space Plaza where statues of satellites and Taikonauts rise from cracked tiles. Murals depict spacewalks and orbital stations, now witnessed only by tumbleweeds and the occasional tourist. A former aerospace plant sits at the edge of town, its blast doors rusted shut, its walls still shouting red slogans praising scientific socialism.

Yumen is where the Space City concept begins to feel ghostly. These places were never built for public access. They were secretive, insular, and highly controlled. Now, stripped of state function, they remain as echoes.

Juan Manuel Lozano utilisant un Rocketbelt

Korla: From Missiles to Markets

Farther west, in the autonomous region of Xinjiang, sits Korla. Unlike Yumen or Jiuquan, Korla is not a ruin. It is a thriving desert city that quietly plays a role in China’s modern space ecosystem. This is the headquarters of the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force’s western command and one of the primary sites for testing ballistic missile technologies.

Though less visibly space-themed, Korla is part of the same lineage. Military-industrial zones here include remnants of early Dongfeng missile tests, which later formed the basis of China’s satellite launch vehicles. The Luobupo People’s Museum, just outside the city, offers a strange juxtaposition—ancient mummies displayed alongside Cold War relics. Here, the arc of Chinese civilization and its modern technological aspirations meet in sand and glass.

Korla may not sell Taikonaut toys in the markets, but its role in the Chinese missile-to-space pipeline is crucial. The city represents the future-facing continuation of what began in the now-crumbling towers of Yumen and Jiuquan.

All about the Space Cities

China Manned Space Engineering Office

The mythology of the space race is usually told through images of Cape Canaveral, Gagarin’s smile, or Buzz Aldrin on the Moon. China’s narrative is more hidden. Its Space Cities are not tourist-friendly, nor are they marketed by the state as heritage zones. Yet they are perhaps the most authentic remnants of a national dream that fused ideology, science, and power.

These sites are not relics of exploration but of confrontation. They were built during an era when China feared invasion, isolation, and nuclear war. Rockets were not for science fiction but survival. The architecture of these cities reflects that mentality: austere, brutalist, defensive.

Today, with China’s space program more advanced than ever—featuring lunar plans, Mars rovers, and a permanent space station—the old Space Cities are fading into obscurity. The official narrative is focused on the future, not the dusty launch bunkers of the past. But for those who want to understand where it all began, and how a nation went from famine to the stars in under two generations, these cities still speak.

They are more than abandoned towns. They are the first real infrastructure of China’s celestial ambition. They are the shadows behind the satellites. They are Space Cities.

Click to check out our China Tours.